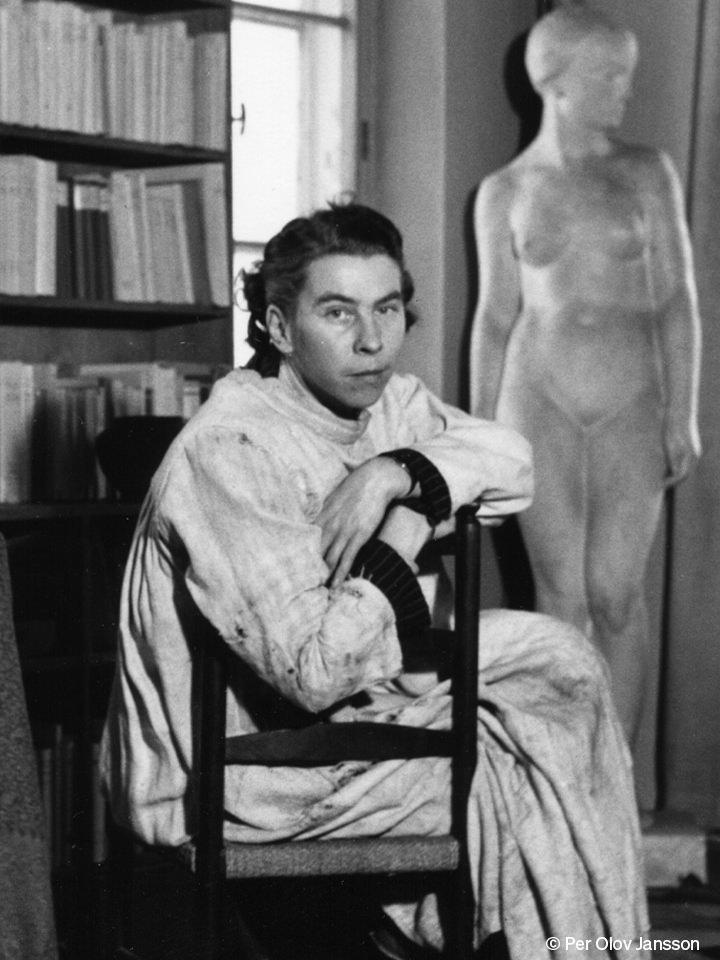

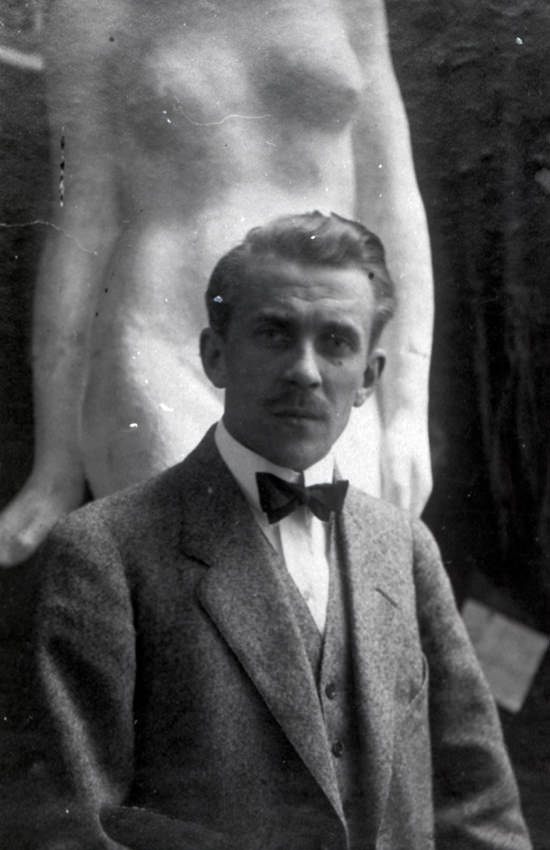

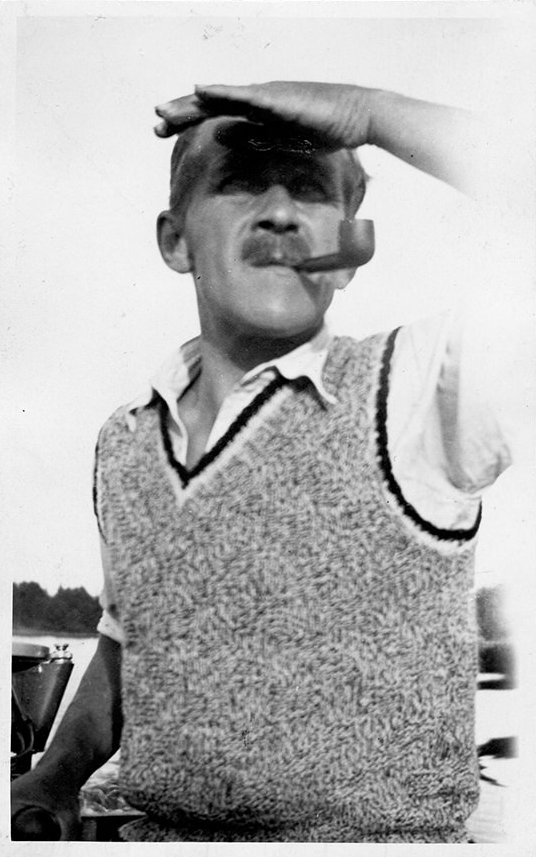

A STORM-LOVING FATHER

“My father was a melancholy man but when a storm threatened he became a different person, cheerful, entertaining and ready to join his children in dangerous adventures.” This is Tove Jansson’s description of her father, the sculptor Viktor Jansson. These adventures might be foraging for mushrooms deep in the forest or watching fires in the middle of the night. As it says in her autobiographically inspired novel Sculptor’s Daughter (1968): “He always woke us up and we heard the fire engine clanging, there was always a great rush and we ran through completely empty streets.”

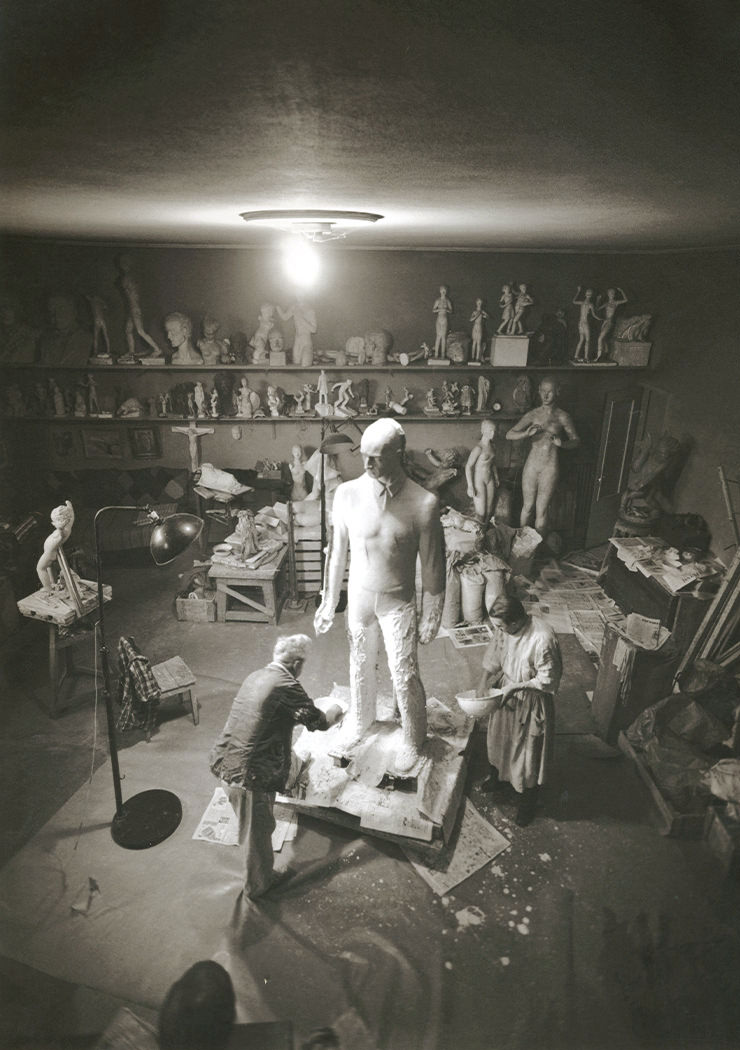

Jansson’s storm-loving father, whose studio was filled with sculptures big and small, was a multi-faceted man. He protected animals such as seagulls, squirrels, crows, bats and marmots, he played the accordion, guitar and balalaika, and he partied all night with his circle of male artist companions. However, he was deeply traumatised by his horrific experiences of fighting on the front line for the Whites in the Finnish Civil War, in the spring and winter of 1918. In January 1928, war broke out between the Reds, largely consisting of working-class socialists, and the Whites, who were mainly the conservative middle class under the leadership of the Finnish Senate. He ran across open battlefields to retrieve ammunition under heavy fire. Hours before his first battle, he wrote to his wife:

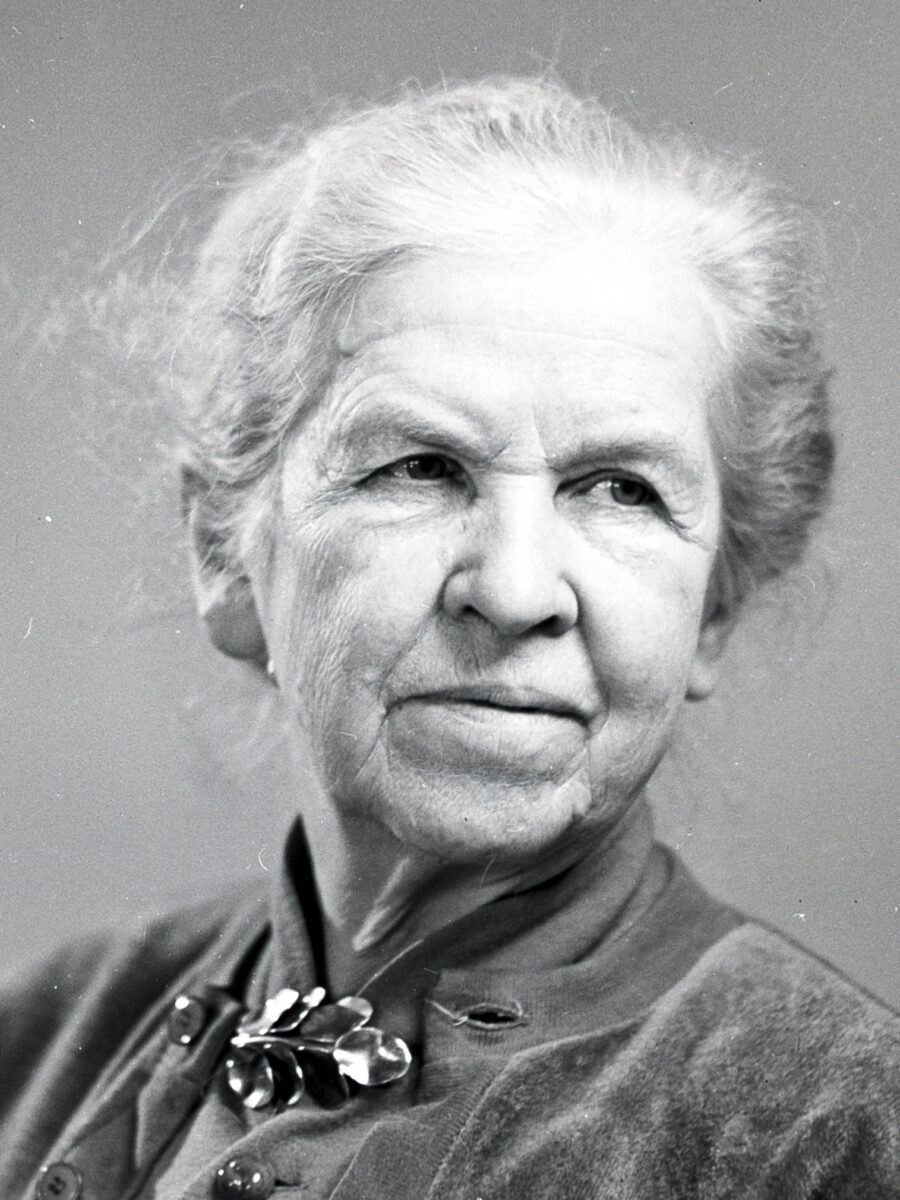

“My dear little Signe. Your husband is about to go into battle. God help us and our weapons. Perhaps I shall never see you again.”

Viktor Jansson’s traumatic wartime experiences affected his family in various ways and found their way into Tove’s childhood memoir Sculptor’s Daughter. Memories could be suppressed during the day, but came spilling out during nocturnal celebrations. “Then Daddy goes and fetches his bayonet which hangs above the sacks of plaster in the studio and everybody jumps up and shouts and Daddy attacks the chair. During the day it is covered with a rug so that you can’t see what it looks like.”

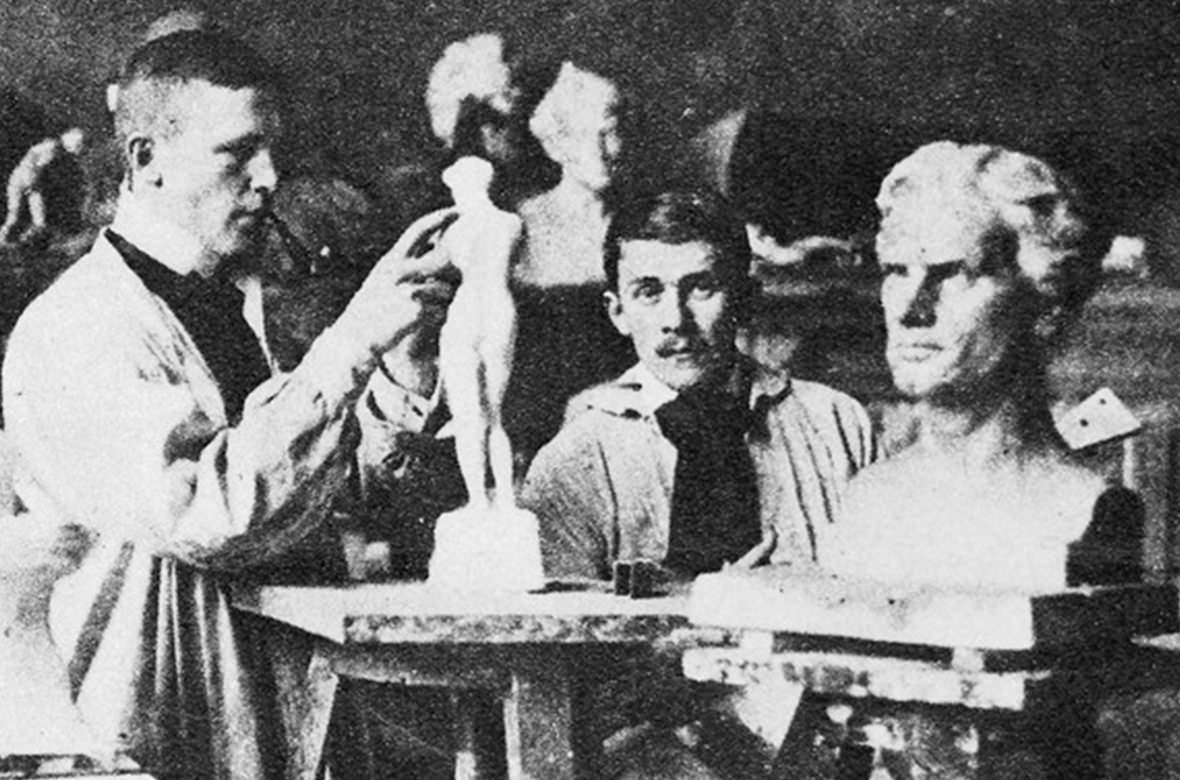

Viktor Jansson took part in the Finnish civil war in 1918 on the side of the whites

Viktor Jansson took part in the Finnish civil war in 1918 on the side of the whites This is Tove Jansson’s description of her father, the sculptor Viktor Jansson. These adventures might be foraging for mushrooms deep in the forest or watching fires in the middle of the night. As it says in her autobiographically inspired novel Sculptor’s Daughter (1968): “He always woke us up and we heard the fire engine clanging, there was always a great rush and we ran through completely empty streets.”

Jansson’s storm-loving father, whose studio was filled with sculptures big and small, was a multi-faceted man. He protected animals such as seagulls, squirrels, crows, bats and marmots, he played the accordion, guitar and balalaika, and he partied all night with his circle of male artist companions. However, he was deeply traumatised by his horrific experiences of fighting on the front line for the Whites in the Finnish Civil War, in the spring and winter of 1918. In January 1928, war broke out between the Reds, largely consisting of working-class socialists, and the Whites, who were mainly the conservative middle class under the leadership of the Finnish Senate. He ran across open battlefields to retrieve ammunition under heavy fire. Hours before his first battle, he wrote to his wife:

“My dear little Signe. Your husband is about to go into battle. God help us and our weapons. Perhaps I shall never see you again.”

Viktor Jansson’s traumatic wartime experiences affected his family in various ways and found their way into Tove’s childhood memoir Sculptor’s Daughter. Memories could be suppressed during the day, but came spilling out during nocturnal celebrations. “Then Daddy goes and fetches his bayonet which hangs above the sacks of plaster in the studio and everybody jumps up and shouts and Daddy attacks the chair. During the day it is covered with a rug so that you can’t see what it looks like.”