Every Canvas is a Self-portrait

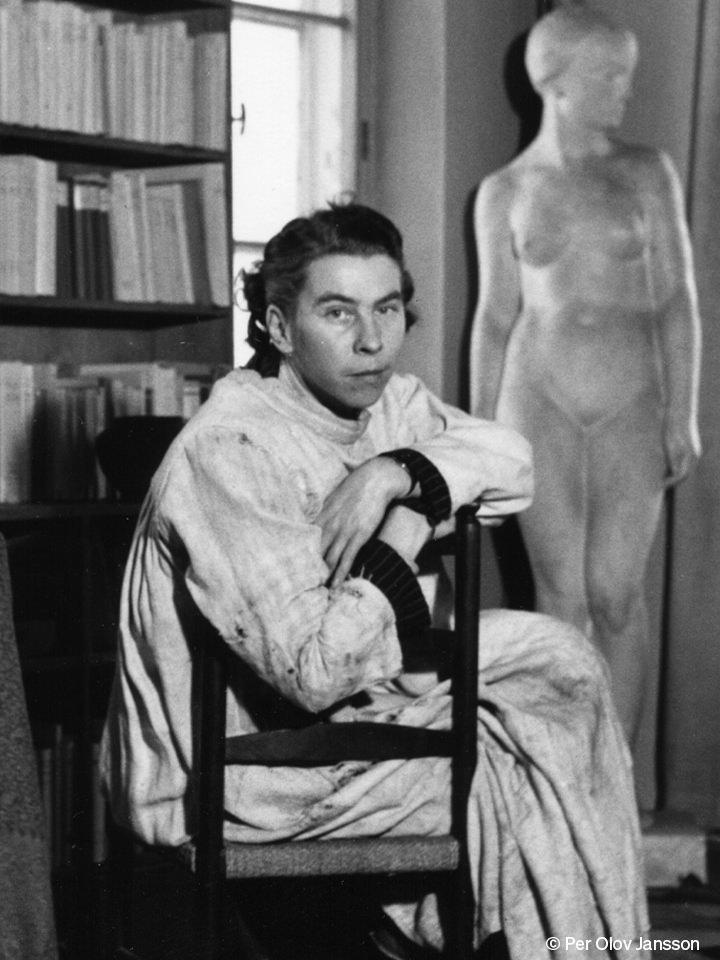

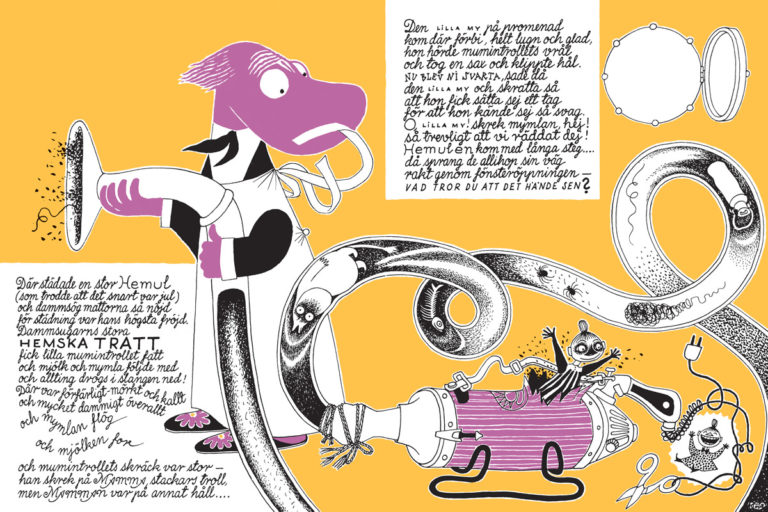

During her art studies in Helsinki and Paris in the 1930s, Tove completes many self-portraits, from charcoal sketches to larger works in oil, adopting the French Colourist and Impressionist styles. Her first self-portrait, a drawing, is included in the exhibition Humoristerna (The Humourists) at Salon Strindberg in 1933. She depicts herself in oil in the background of her own paintings.

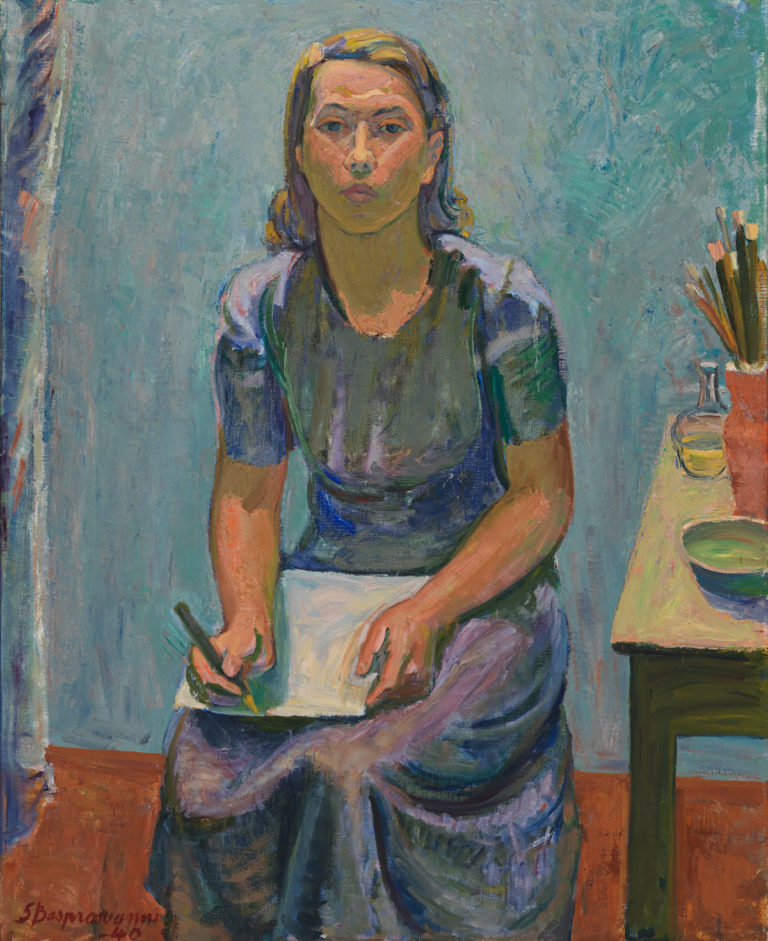

Girl Smoking (Self-portrait, Rökande flicka), Tove Jansson 1940.

Tove Jansson does not always enjoy being a student; she takes breaks, enrolls in other colleges, and, along with her peers, is critical of the rigid and hierarchical teaching styles she encounters. However, she learns and makes valuable contacts.

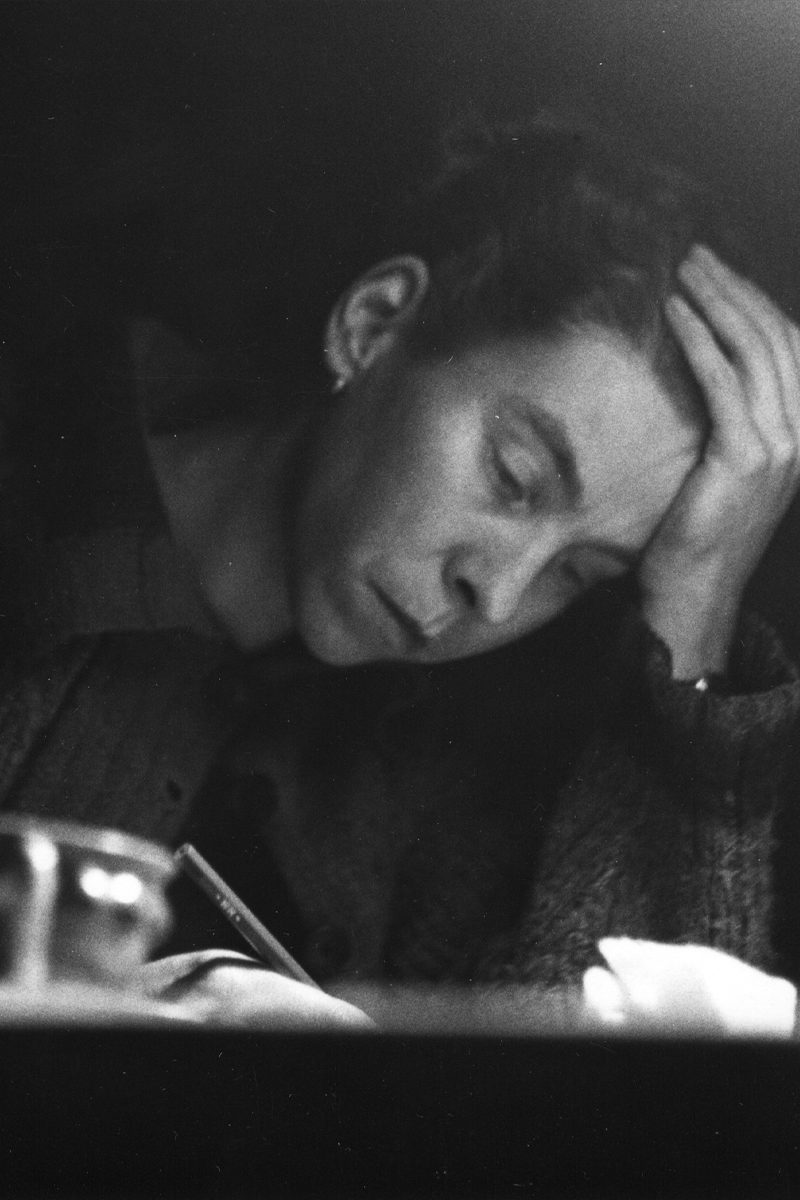

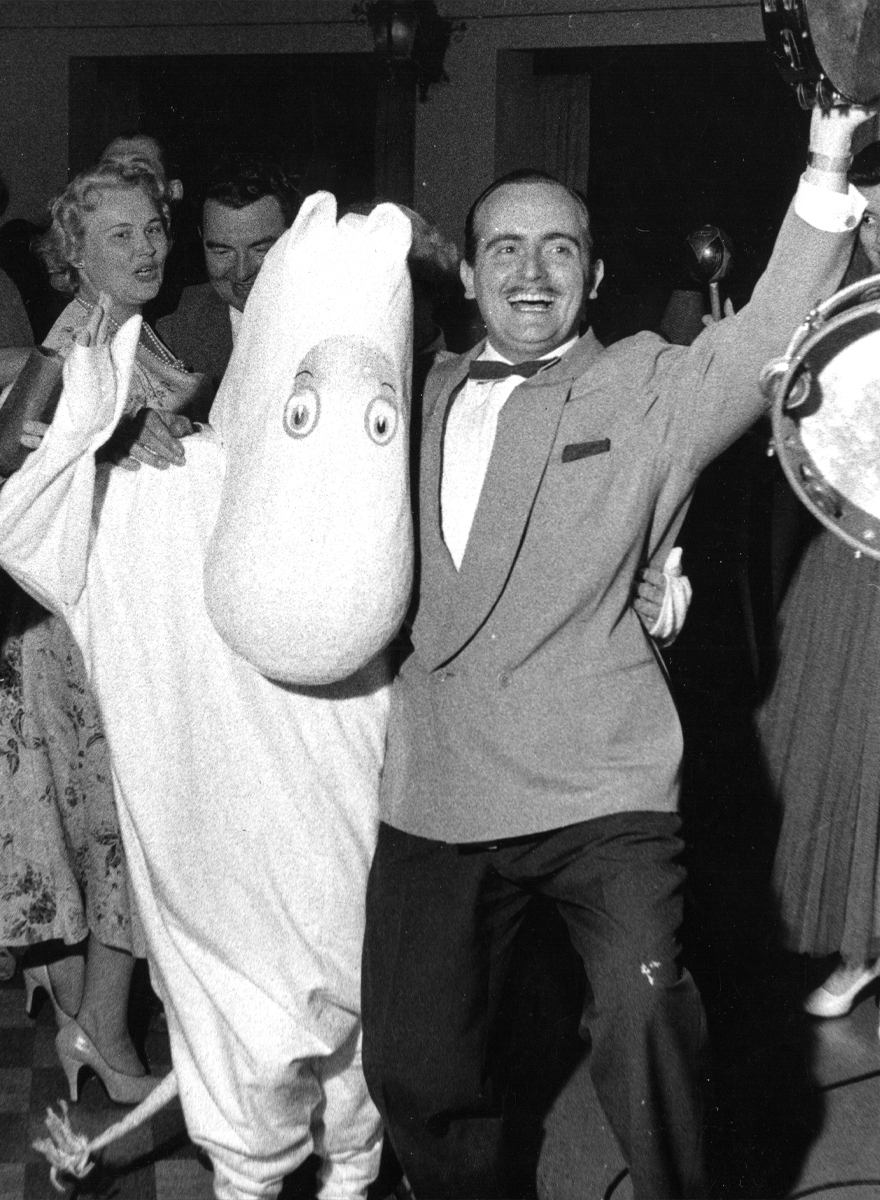

One of her closest friends is the artist Sam Vanni (Samuel Besprosvanni), who becomes her mentor and lover. She draws him in charcoal, and in return, he paints her in oils.

No two Tove Jansson self-portraits are alike. She experiments with different techniques and with her identity and role as an artist and a woman. In the early 1940s, she paints a picture of herself gazing out from the canvas to the viewer. She is wearing a leather cap and a fur coat in what seems an explicit reference to the portraits of Rembrandt. It is as if she is presenting herself as a self-assured woman engaged in a dialogue with the master of fine art, ready and able to meet the demands of her craft. At the same time, she is critical of the work, describing her facial expression as derisive and rigid.

Tove Jansson portrayed by Sam Vanni, 1940.

Lynx boa (self-portrait), Tove Jansson 1942.

Tove Jansson had already established herself in the Helsinki fine art scene, as well as gaining fame as an illustrator and storyteller, when she titles a new self-portrait ‘The Beginner’. This is her first abstract work and a bold new departure. She begins to sign her paintings with her last name, instead of the more familiar ‘Tove’. She is willing to be humble in her approach to art and ready to start again from scratch.

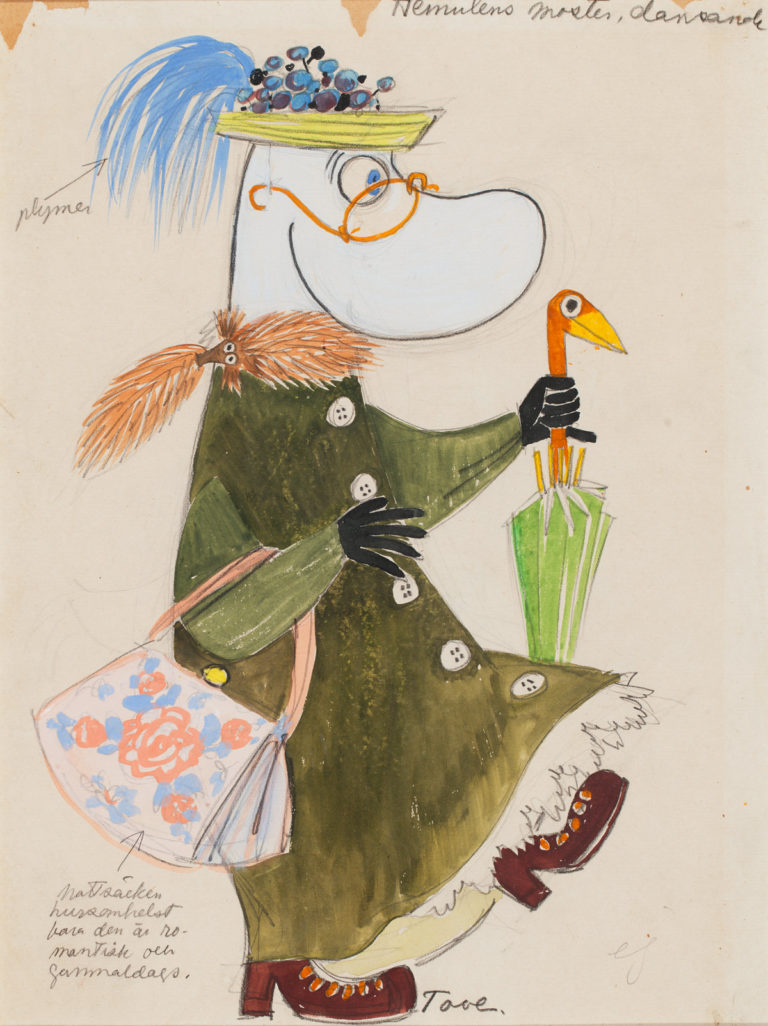

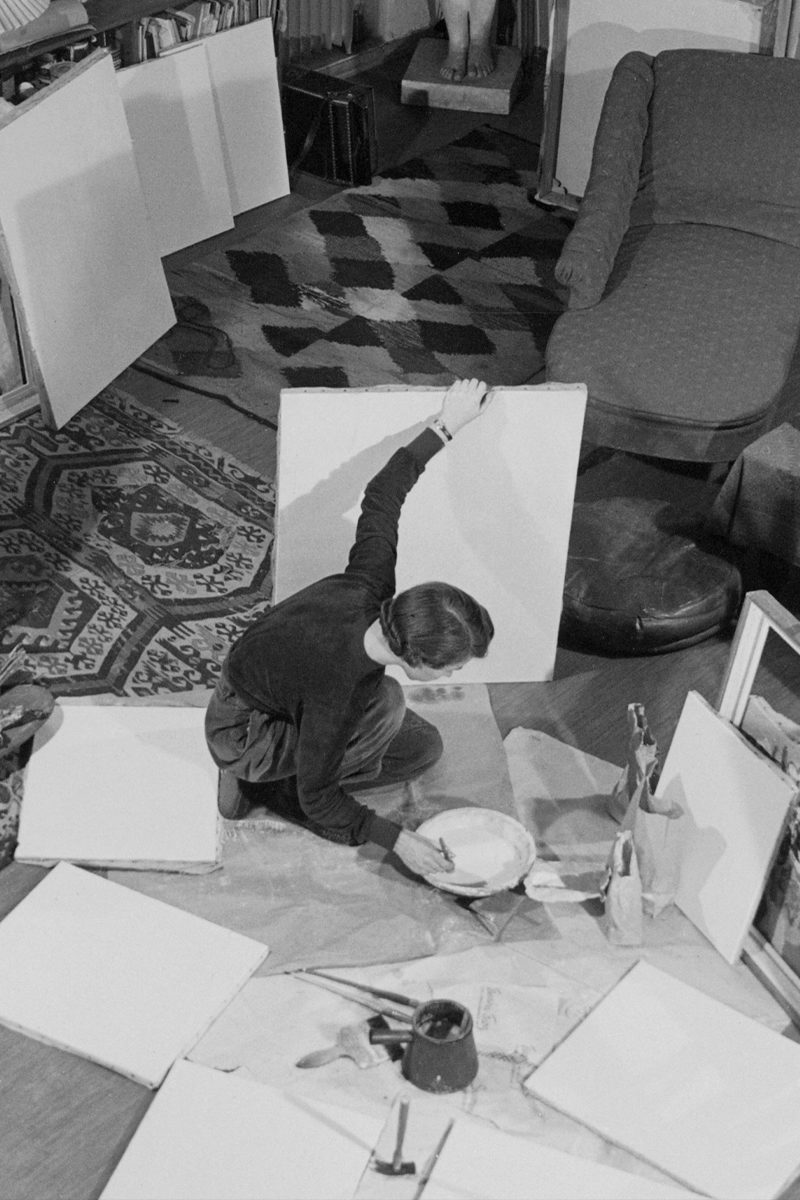

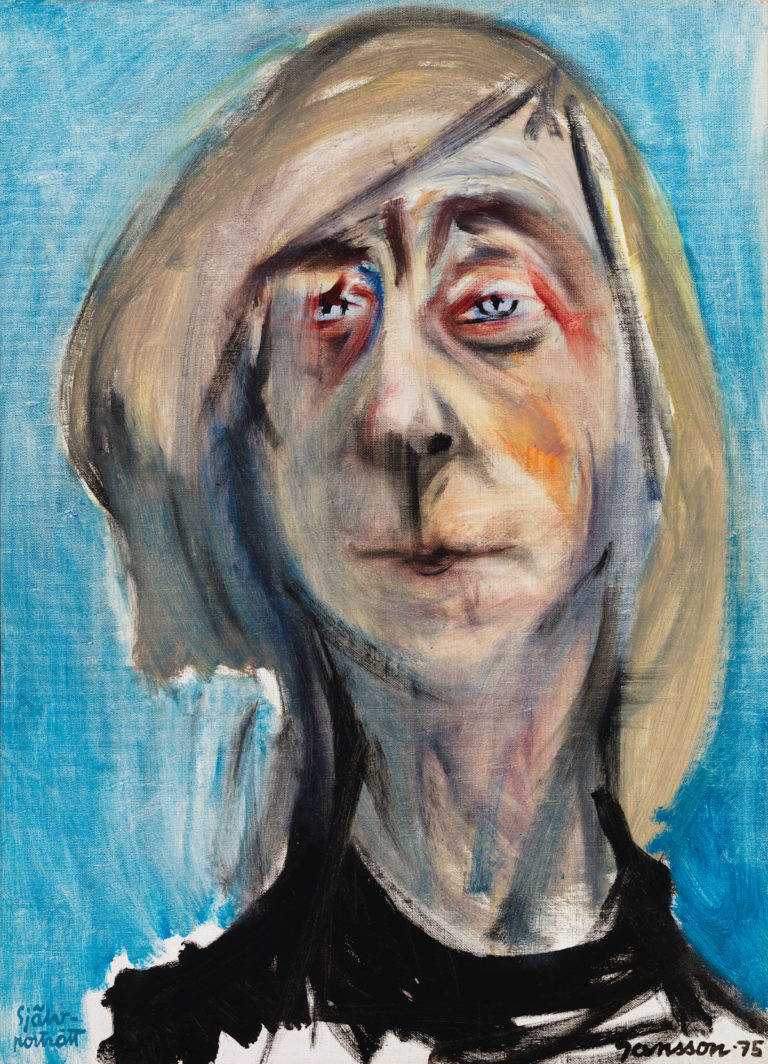

The 1960s are a creative period for Tove Jansson the artist, but they are followed by a long pause in painting, where her writing and illustration – and the whole enterprise of the Moomins – takes precedence. However, in the mid-1970s, while accompanying Tuulikki Pietilä on an artist’s residence in Paris, she is surprised to find that the urge to paint has returned. She takes up her brushes and captures herself in an inquisitive oil portrait. Her strokes are broad and enjoyable; she is set free to looks at herself with detachment.

Tove Jansson self portrait (1975).

Tove Jansson self portrait (1975). The painting from these days by the Seine was Tove Jansson’s last self-portrait; it was included in her last exhibition in 1975. In this way, she comes full circle from her earliest sketches.

Tove Jansson’s self-portraits reflect the development of her identity, her susceptibility to change, and her view of herself as an artist.

During her art studies in Helsinki and Paris in the 1930s, Tove completes many self-portraits, from charcoal sketches to larger works in oil, adopting the French Colourist and Impressionist styles. Her first self-portrait, a drawing, is included in the exhibition Humoristerna (The Humourists) at Salon Strindberg in 1933. She depicts herself in oil in the background of her own paintings.

Tove Jansson does not always enjoy being a student; she takes breaks, enrols in other colleges, and, along with her peers, is critical of the rigid and hierarchical teaching styles she encounters. However, she learns and makes valuable contacts.

One of her closest friends is the artist Sam Vanni (Samuel Besprosvanni), who becomes her mentor and lover. She draws him in charcoal, and in return, he paints her in oils.

No two Tove Jansson self-portraits are alike. She experiments with different techniques and with her identity and role as an artist and a woman. In the early 1940s she paints a picture of herself gazing out from the canvas to the viewer. She is wearing a leather cap and a fur coat in what seems an explicit reference to the portraits of Rembrandt. It is as if she is presenting herself as a self-assured woman engaged in a dialogue with the master of fine art, ready and able to meet the demands of her craft. At the same time, she is critical of the work, describing her facial expression as derisive and rigid.

Tove Jansson had already established herself in the Helsinki fine art scene, as well as gaining fame as an illustrator and storyteller, when she titles a new self-portrait ‘The Beginner’. This is her first abstract work and a bold new departure. She begins to sign her paintings with her last name, instead of the more familiar ‘Tove’. She is willing to be humble in her approach to art and ready to start again from scratch.

The 1960s are a creative period for Tove Jansson the artist, but they are followed by a long pause in painting, where her writing and illustration – and the whole enterprise of the Moomins – takes precedence. However, in the mid-1970s, while accompanying Tuulikki Pietilä on an artist’s residence in Paris, she is surprised to find that the urge to paint has returned. She takes up her brushes and captures herself in an inquisitive oil portrait. Her strokes are broad and enjoyable; she is set free to looks at herself with detachment.

The painting from these days by the Seine was Tove Jansson’s last self-portrait; it was included in her last exhibition in 1975. In this way, she comes full circle from her earliest sketches.

Tove Jansson’s self-portraits reflect the development of her identity, her susceptibility to change, and her view of herself as an artist.