Tove Jansson and anti-fascism

Travels through Germany

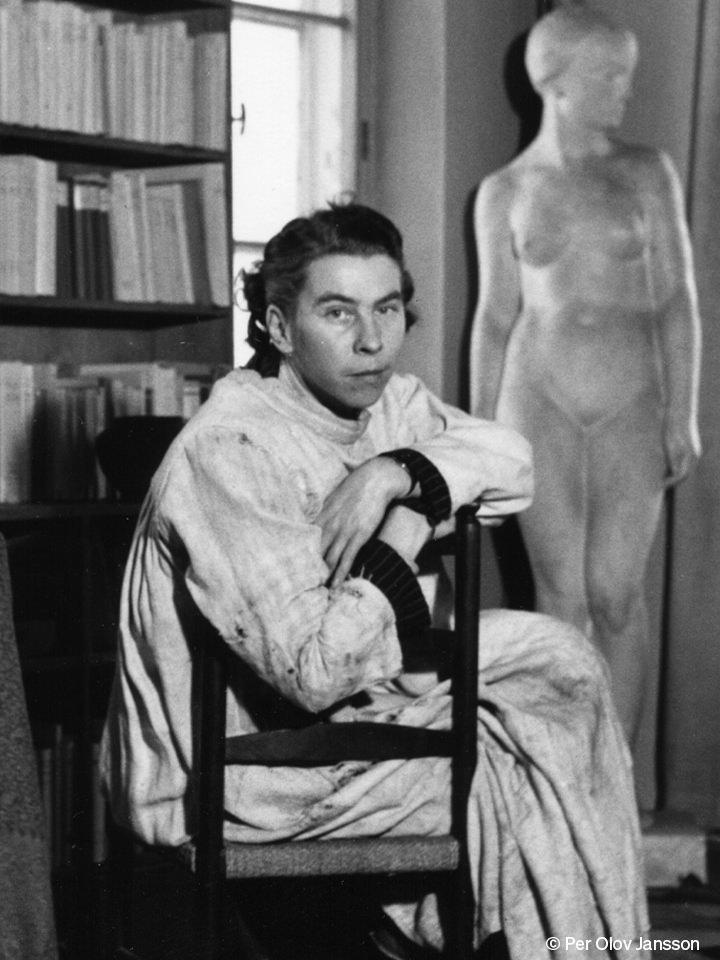

It is the 1930s and very unusual for a young woman to travel alone. But since Tove Jansson has relatives in Velbert, Germany, she takes the opportunity to travel across the continent in 1934. She notices the widespread nationalist spirit and illustrates it in her notebooks. As she travels through Nuremberg, she depicts a distinctly hostile city.

The image of Germany she creates is far from romanticised. In the short story Brevet [The Letter], she expresses the horrors of life in Munich through the impoverished and unhappy Mr Vöpel who has sunk into a “grey cloak of meaninglessness.” Unable to afford travel, he looks enviously upon the happy globe-trotters at the train station.

Tove Jansson considers herself a liberal, joking that she is hopelessly bourgeois, despite the fact that her father calls her left-wing on account of the sort of company she keeps. In her social life among the Helsinki literati of the late 1930s, conversations are increasingly moving from art to politics and the impending war.

Dolls doing a Nazi greeting in Tove Jansson’s illustration for Garm, 1935.

Tove Jansson’s Nazi sketch while traveling in Germany, 1934.

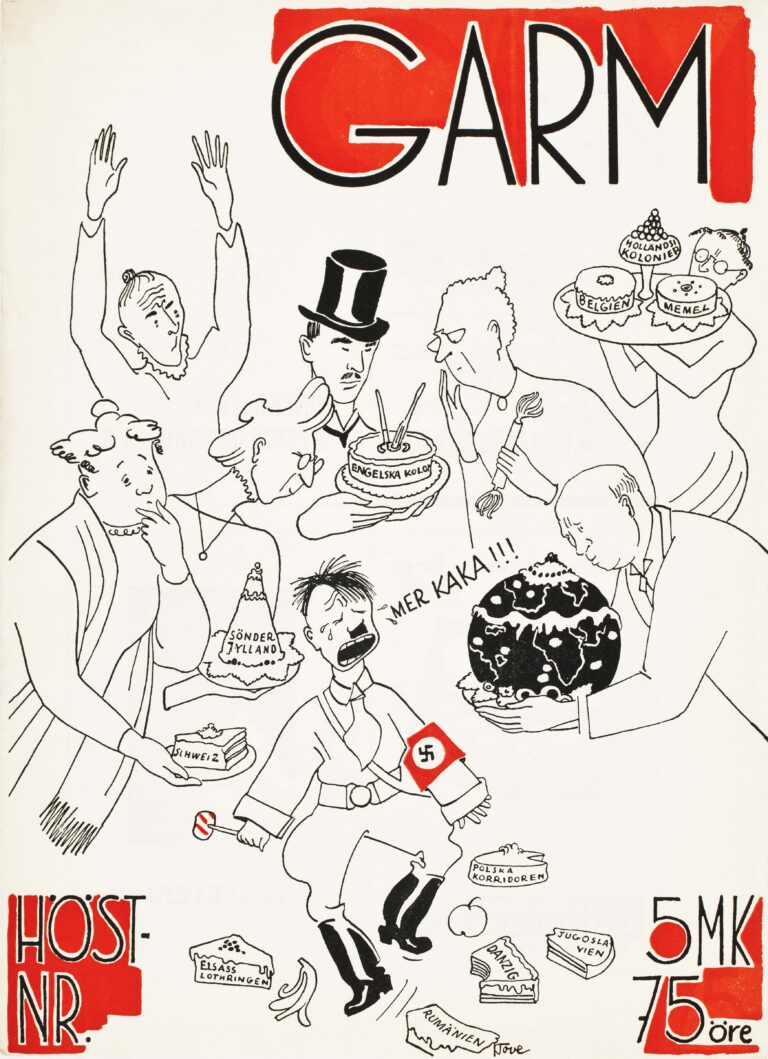

Hitler cries: “More cake!!!”

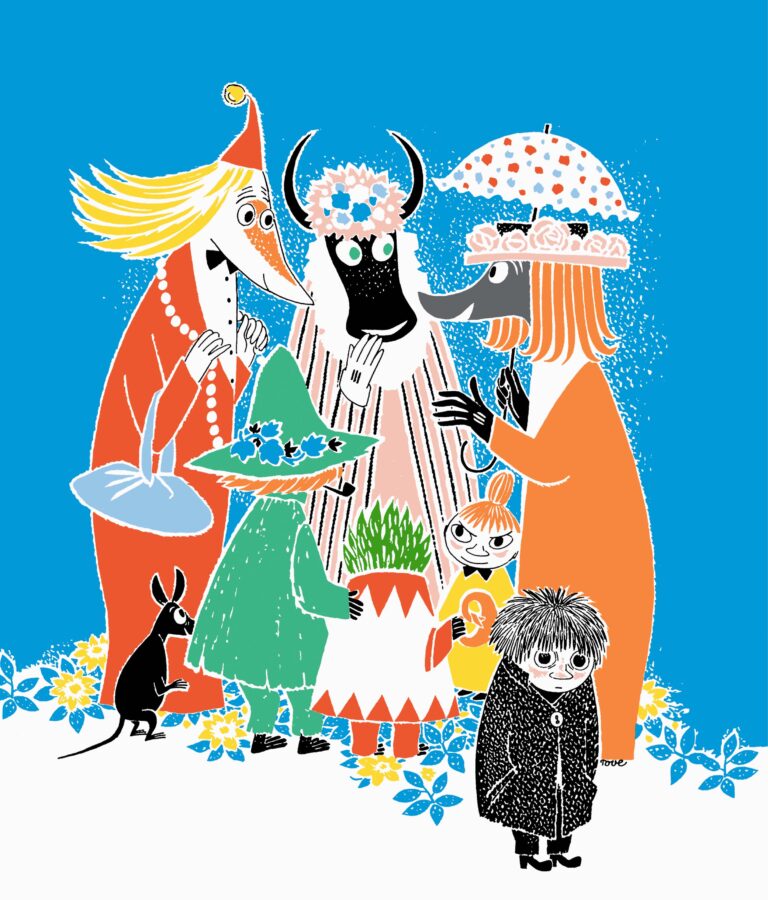

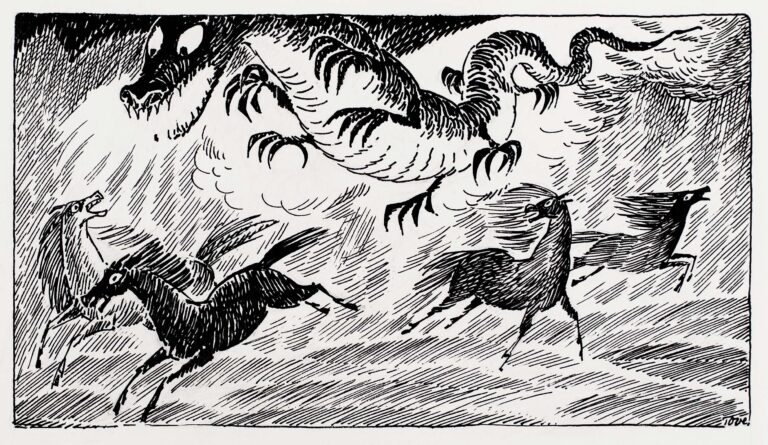

As early as 1935, Tove Jansson produces an illustration for Garm wherein a customer wants to buy a doll that says “mama”, but the toy shop exclusively stocks dolls that say “Heil Hitler.” The spread of fascism is seeping into the everyday lives of normal members of society, including women and children, and having a concrete effect. Garm is a progressive satirical magazine, outspokenly critical of dictatorship, with anti-fascism as one of their core values.

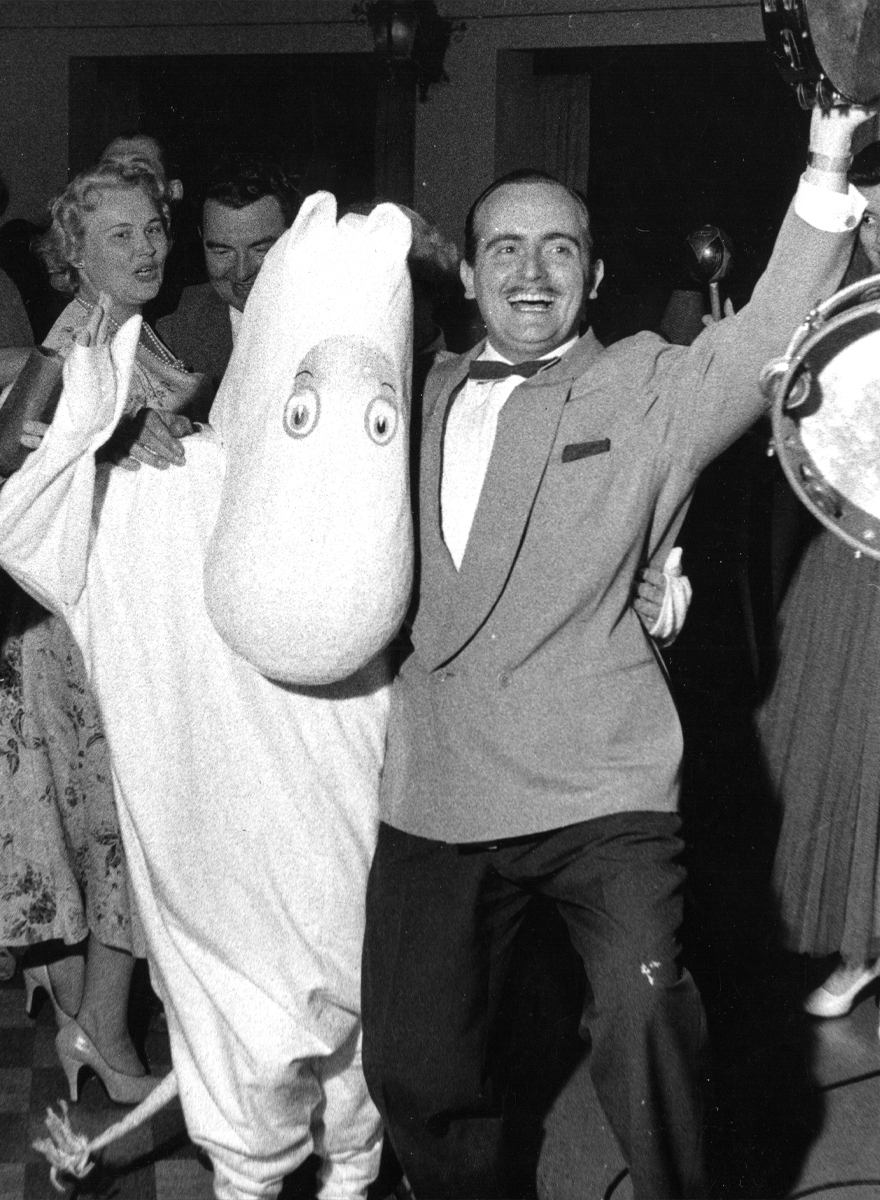

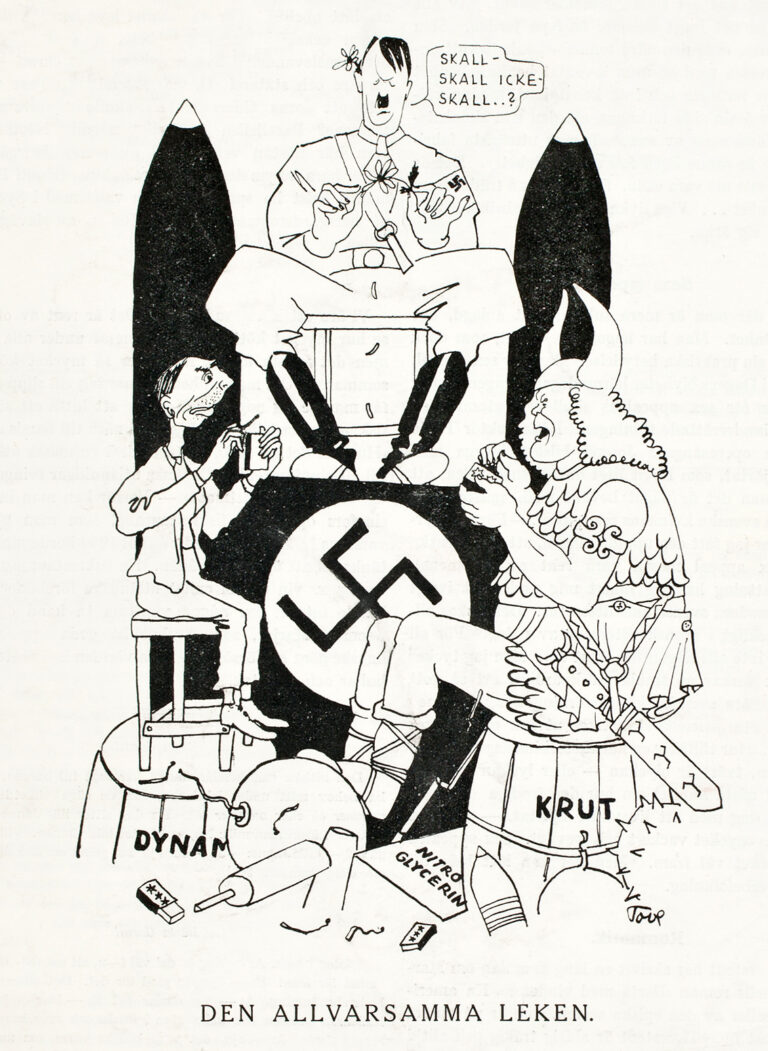

Tove Jansson first appears on the cover of Garm in 1938, with a startling image of Hitler sitting on top of a warehouse of explosives. This is the year that the German army expands into Central Europe, and at the fateful Munich Conference, Hitler is given free rein in Czechoslovakia. Just a few weeks later, Tove Jansson portrays the German Führer as a spoiled child, surrounded by adults trying to appease him with cakes. Hitler cries: “More cake!!!” while surrounded by cakes with names like Alsace-Lorraine and the Polish Corridor.

Tove Jansson’s Hitler illustration for Garm cover, 1938.

These restrictive boundaries, this racial hatred

Tove Jansson also speaks out when fascism rears its ugly head in unexpected situations. While studying in Paris in the mid-30s, she spends time in Le Dôme Café with people who turn out to be Finnish nationalists (so-called “genuine Finns”). In a letter to her family, she writes:

“I didn’t say a word for an hour and a half, but then I couldn’t hold it in any longer and told them it was the curse of the world, these restrictive boundaries, this racial hatred, this linguistic baiting, this petty ‘you-can’t-play-in-our-yard’, this ludicrous labelling, and next time they showed any tendency to start hacking on about politics, I would just get up and leave.” Letters from Tove

In 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, Tove Jansson takes a trip to Italy. After staying in a hotel called Germania, she is inspired to pen the short story Aldrig mera Capri [Never Again Capri!] in which the island is invaded by German tourists. “Aryan white and hygienic all around,” the narrator thinks, wondering where authentic Italy is hiding and why on earth she has come to Italy to eat German cuisine.

Tove Jansson’s Hitler illustration for Garm (Den allvarsamma leken), 1938.

Censored Stalin

While stuck in Helsinki during the war in the 1940s, Tove Jansson increases her contributions to Garm. She often includes the infamous swastika on her cover illustrations and makes copious allusions to the atrocities of her native country.

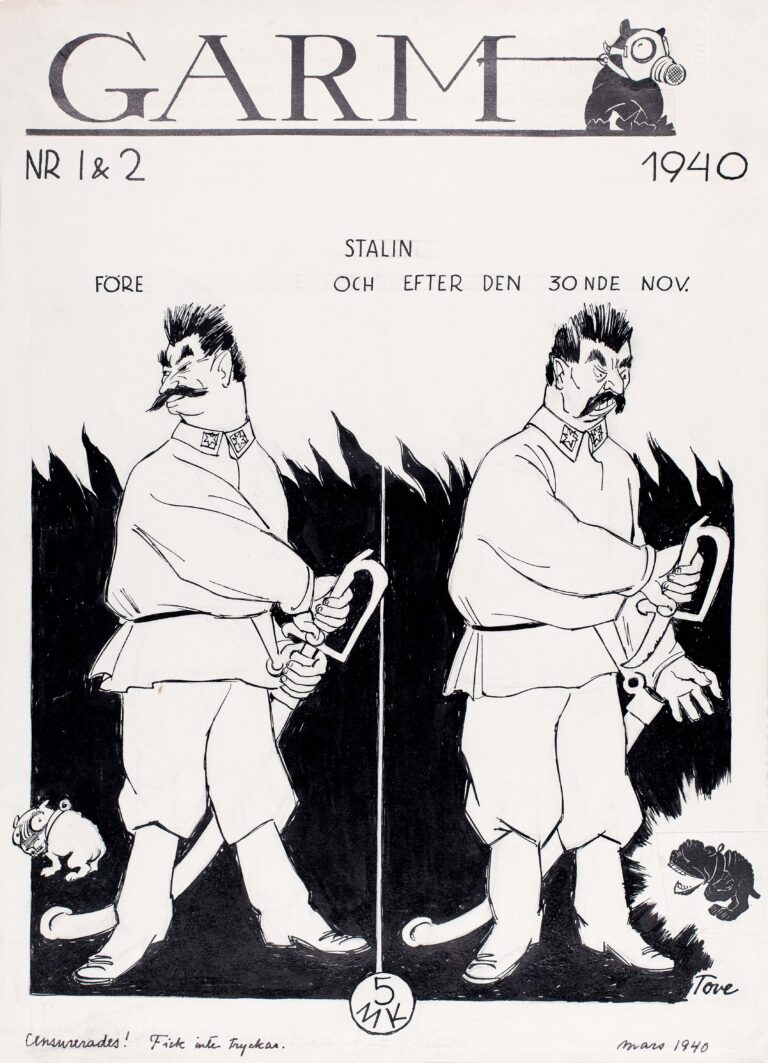

During the peace negotiations between Finland and the Soviet Union, her depiction of Stalin is censored. The illustration for Garm (1940 no. 1 & 2) jokes about the size of Stalin’s sword. For the picture to be approved, she has to change his physicality and give him a bushy beard, so that he might be interpreted as any typical Russian soldier.

But drawing caricatures of famous people is only a tiny fraction of Tove Jansson’s work. Portraits are not her main strength, after all. Most of her pictures for Garm deal with everyday life in a war-torn country and the experiences of the ordinary individual. In the New Year issue of 1943, she depicts the old year 1942 with its arms full of war-related debris, which it hands over to the innocent year 1943. She shows eternal sympathy for those crushed under the burdens of war, coupled with a talent for representing the absurd, and even comical, in ever more trying times.

Tove Jansson’s Stalin illustration for Garm cover, 1939.

Travels through Germany

It is the 1930s and very unusual for a young woman to travel alone. But since Tove Jansson has relatives in Velbert, Germany, she takes the opportunity to travel across the continent in 1934. She notices the widespread nationalist spirit and illustrates it in her notebooks. As she travels through Nuremberg, she depicts a distinctly hostile city.

The image of Germany she creates is far from romanticised. In the short story Brevet [The Letter], she expresses the horrors of life in Munich through the impoverished and unhappy Mr Vöpel who has sunk into a “grey cloak of meaninglessness.” Unable to afford travel, he looks enviously upon the happy globe-trotters at the train station.

Tove Jansson considers herself a liberal, joking that she is hopelessly bourgeois, despite the fact that her father calls her left-wing on account of the sort of company she keeps. In her social life among the Helsinki literati of the late 1930s, conversations are increasingly moving from art to politics and the impending war.

Hitler cries: “More cake!!!”

As early as 1935, Tove Jansson produces an illustration for Garm wherein a customer wants to buy a doll that says “mama”, but the toy shop exclusively stocks dolls that say “Heil Hitler.” The spread of fascism is seeping into the everyday lives of normal members of society, including women and children, and having a concrete effect. Garm is a progressive satirical magazine, outspokenly critical of dictatorship, with anti-fascism as one of their core values.

Tove Jansson first appears on the cover of Garm in 1938, with a startling image of Hitler sitting on top of a warehouse of explosives. This is the year that the German army expands into Central Europe, and at the fateful Munich Conference, Hitler is given free rein in Czechoslovakia. Just a few weeks later, Tove Jansson portrays the German Führer as a spoiled child, surrounded by adults trying to appease him with cakes. Hitler cries: “More cake!!!” while surrounded by cakes with names like Alsace-Lorraine and the Polish Corridor.

These restrictive boundaries, this racial hatred

Tove Jansson also speaks out when fascism rears its ugly head in unexpected situations. While studying in Paris in the mid-30s, she spends time in Le Dôme Café with people who turn out to be Finnish nationalists (so-called “genuine Finns”). In a letter to her family, she writes:

“I didn’t say a word for an hour and a half, but then I couldn’t hold it in any longer and told them it was the curse of the world, these restrictive boundaries, this racial hatred, this linguistic baiting, this petty ‘you-can’t-play-in-our-yard’, this ludicrous labelling, and next time they showed any tendency to start hacking on about politics, I would just get up and leave.” Letters from Tove

In 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, Tove Jansson takes a trip to Italy. After staying in a hotel called Germania, she is inspired to pen the short story Aldrig mera Capri [Never Again Capri!] in which the island is invaded by German tourists. “Aryan white and hygienic all around,” the narrator thinks, wondering where authentic Italy is hiding and why on earth she has come to Italy to eat German cuisine.

Censored Stalin

While stuck in Helsinki during the war in the 1940s, Tove Jansson increases her contributions to Garm. She often includes the infamous swastika on her cover illustrations and makes copious allusions to the atrocities of her native country.

During the peace negotiations between Finland and the Soviet Union, her depiction of Stalin is censored. The illustration for Garm (1940 no. 1 & 2) jokes about the size of Stalin’s sword. For the picture to be approved, she has to change his physicality and give him a bushy beard, so that he might be interpreted as any typical Russian soldier.

But drawing caricatures of famous people is only a tiny fraction of Tove Jansson’s work. Portraits are not her main strength, after all. Most of her pictures for Garm deal with everyday life in a war-torn country and the experiences of the ordinary individual. In the New Year issue of 1943, she depicts the old year 1942 with its arms full of war-related debris, which it hands over to the innocent year 1943. She shows eternal sympathy for those crushed under the burdens of war, coupled with a talent for representing the absurd, and even comical, in ever more trying times.