TOVE JANSSON’S BOLDNESS – AMONG GHOSTS AND MYMBLES

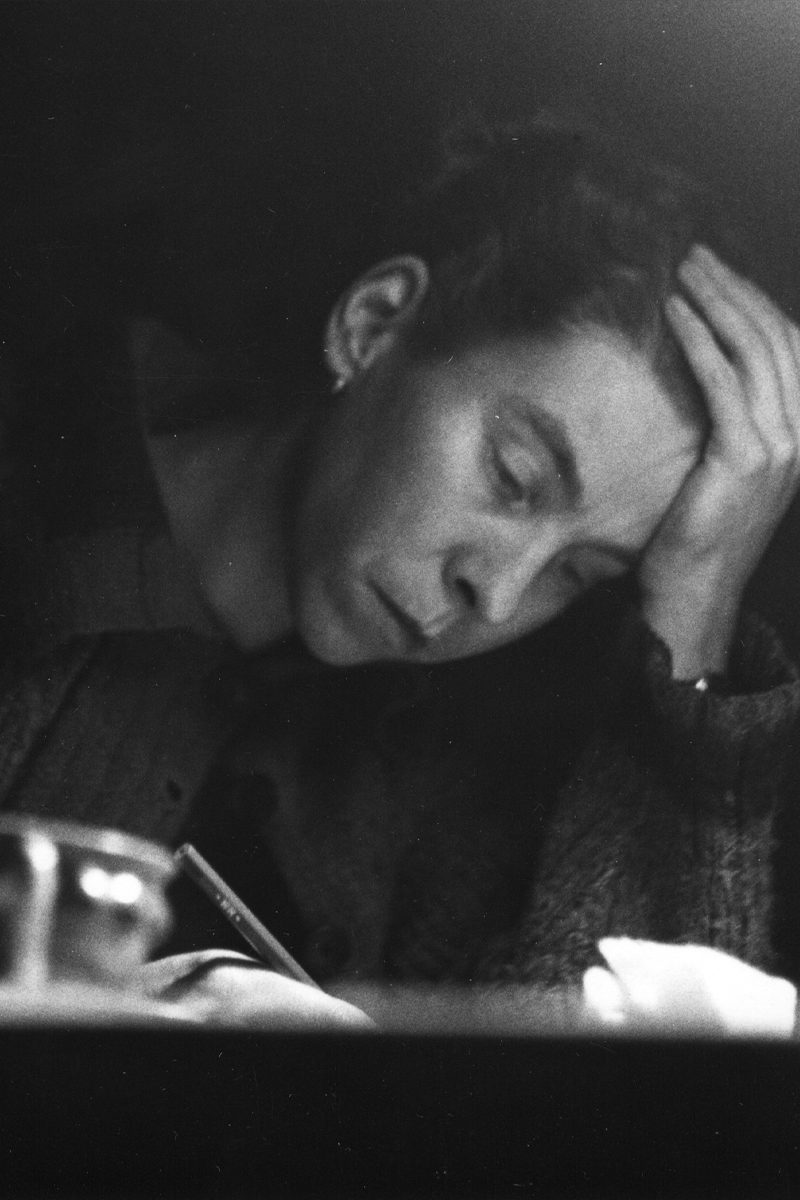

“Vi, I myself am a sun”

Falling in love has changed Tove Jansson. So says her friend Eva Wichman: “You’re different through and through, your manner, your face, the way you move – maybe your thoughts?” (Jansson relates Wichman’s words in a letter to Bandler 29/12/1946). At this point in time, homosexuality is illegal in Finland, and Jansson includes in her letters instructions to burn after reading.

Previously, Tove Jansson has waited for others to approach her and encourage her to bask in the sunshine, whereas with Bandler, she feels already filled with warmth and radiance: “Vi, I myself am a sun.” (Letter to Vivica Bandler) Layers of self-deception and naivety are peeled away to reveal a bold confidence. The communication they share is special, and they fulfil each other’s needs for eroticism, tenderness and understanding.

Alas, Vivica Bandler is soon to depart on a long-planned trip abroad this Christmas. In Tove Jansson’s many love letters to her, she expresses that she is happier than ever. “It is only that happiness is always so serious.” (Letter to Vivica Bandler) Love is not only footloose and fancy-free, but also about loyalty and security. That same evening, she tells Atos Wirtanen, her fiancé at the time, that she no longer loves him.

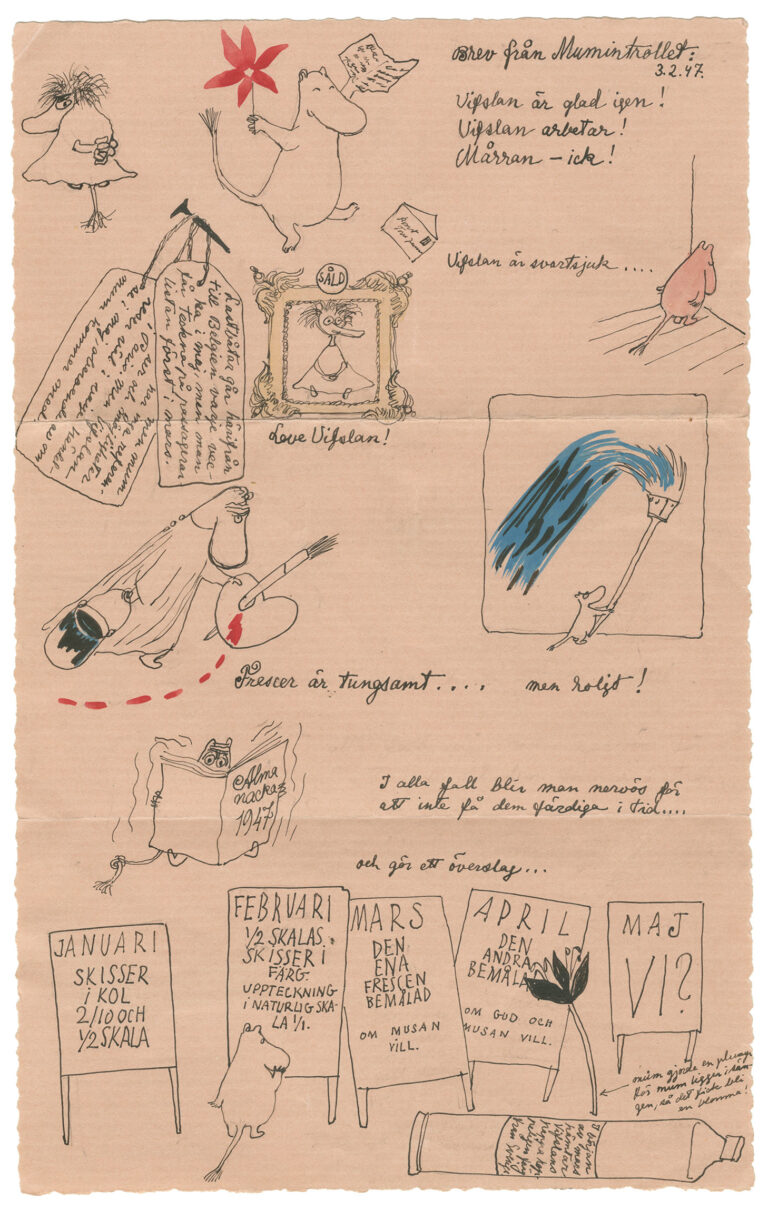

Tove Jansson's letter to Vivica Bandler in 1947, wherein Moomintroll states that it's hard, but a lot of fun, to paint frescos.

Tove Jansson's letter to Vivica Bandler in 1947, wherein Moomintroll states that it's hard, but a lot of fun, to paint frescos. Al fresco and Songs for my Beloved

Agronomist and director Vivica Bandler is married to Kurt Bandler and has mistresses in Helsinki and Paris. Their whirlwind love affair ends in heartbreak for Tove. To avoid arousing suspicion, several days’ worth of letters are sent in one envelope and the address is written by different people each time, from the local shop or hairdresser. Tove Jansson writes about Thingumy and Bob, who speak a language of their own, in what will become Finn Family Moomintroll, and composes love poems that she wishes she could set to music. She also starts planning two large murals for Helsinki City Hall, commissioned by Vivica Bandler’s father, local politician Erik von Frenckell.

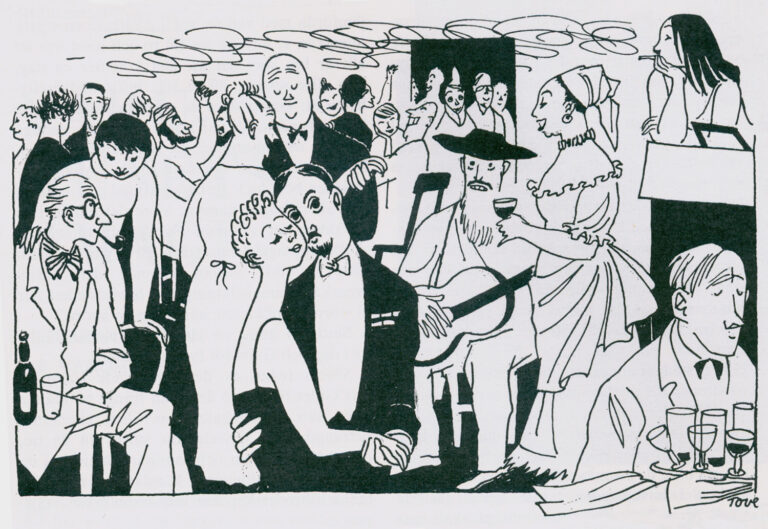

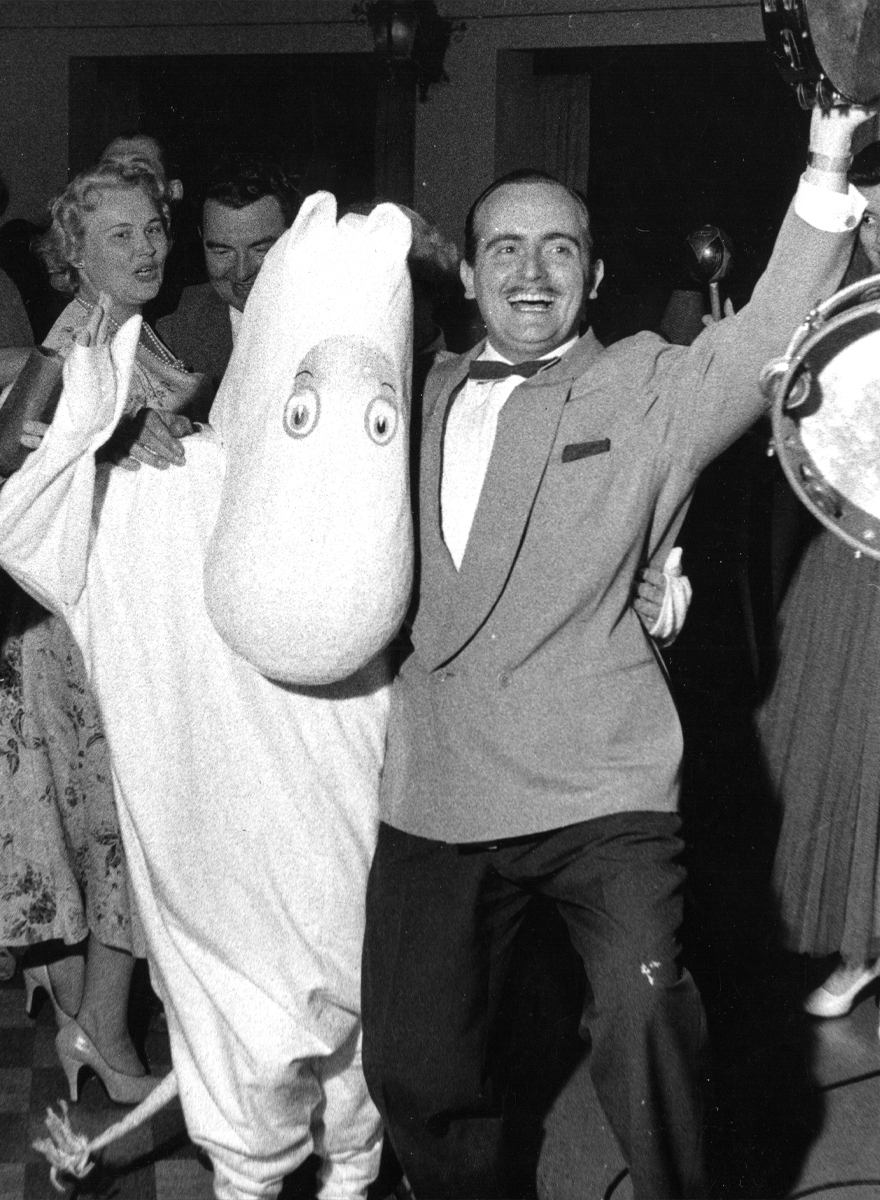

While Jansson is painting her first fresco, Bandler is directing her first film in Paris. Tove Jansson’s friend and mentor Sam Vanni casts doubt on whether she will have time to complete two 2×6 metre large murals in one spring, but she is bold and unfazed. She is keen to prove that she is capable! Johannes Gebhard, teacher of material science at Finnish Art Society’s Drawing School (Ateneum), agrees that it is the opportunity of a lifetime. The task unites her identity and integrity, while also communicating what her beloved means to her. In Party in the City, a very recognisable image of Vivica Bandler dances in the foreground. When Bandler forsakes Tove Jansson for other lovers, her disappointment is great. Their period of happiness is bordered by dark carmine, just as love is edged with darkness.

In the fresco Party in the City, the dark haired Vivica Bandler is dancing while Tove Jansson is smoking a cigarette in the foreground. The fresco is nowadays part of the permanent exhibition at HAM, the Helsinki Art Museum.

In the fresco Party in the City, the dark haired Vivica Bandler is dancing while Tove Jansson is smoking a cigarette in the foreground. The fresco is nowadays part of the permanent exhibition at HAM, the Helsinki Art Museum. “Her dress is painted bright and fine

as was our time so glad,

but all around is dark carmine

and the blackest paint I had.”

(“Al Fresco” from Visor till min käresta, translated by Annie Prime)

Visor till min käresta (Songs for my Beloved, later titled Visor till min dam, Songs for my Lady) is an unpublished collection of verses expressing pain, longing, intense joy, admiration and profound melancholy. Tove Jansson sends the text to Vivica Bandler the same summer she gives up on their love. In the poems, the narrator merges into her lover’s wallpaper to hide from all the ‘ifs’, ‘shoulds’ and ‘buts’, but finally sails away in a blue boat when she can no longer stand it.

Contramystical lament

Little by little, Jansson and Bandler’s relationship transforms into a close friendship and mutual support. They are both intense characters, curious about people and united by their creative work. They also share a sense of humour. A year after Tove Jansson sent Songs for my Beloved to Vivica Bandler, she sends her a light-hearted, avant-garde illustrated text entitled Fittornas återtåg (Return of the Cunts).

“Return of the cunts

or

Contramystical lament under extreme circumstances

Psychological sexual tragedy in one act with cockful scenery,

intended for minors of poor disposition at Christmas time,

by Thingumy”

It is a romantic piece mixing Dadaism with the underground, with cut-out images of scantily clad ladies and gentlemen. It’s an example of burlesque humour. The mood is good-natured and light-hearted, and the plot revolves around the Pro Vivica association, headed up by Vivica, busy recruiting new members who must be careful not to fall in love with her.

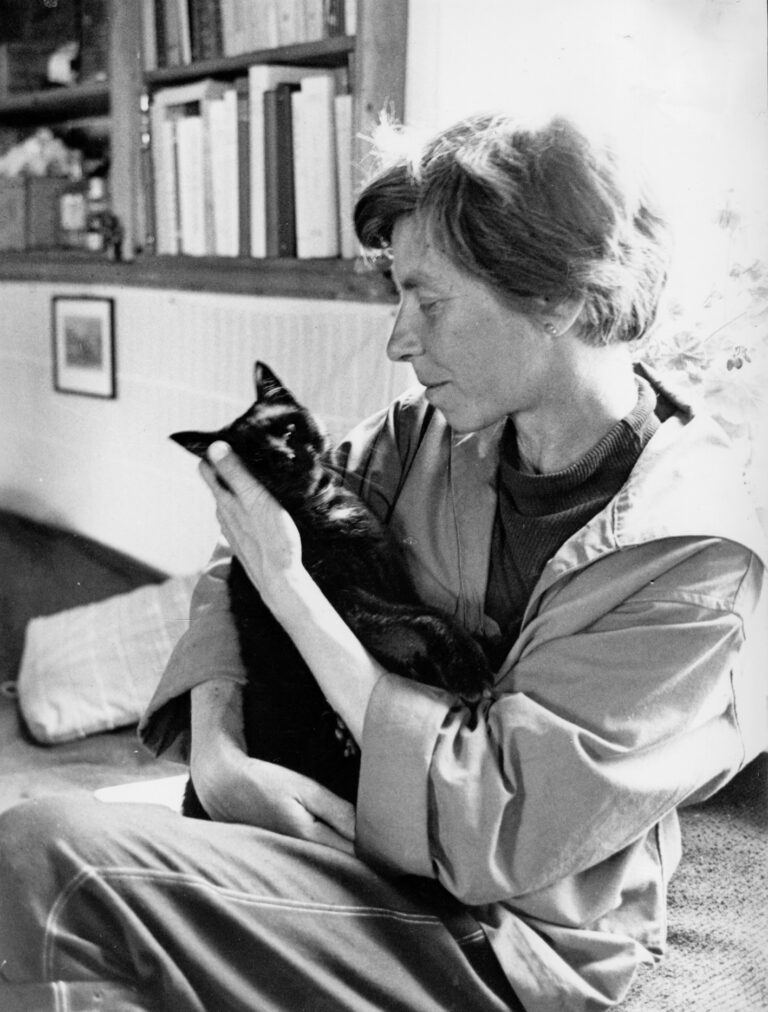

Friends and Mymbles

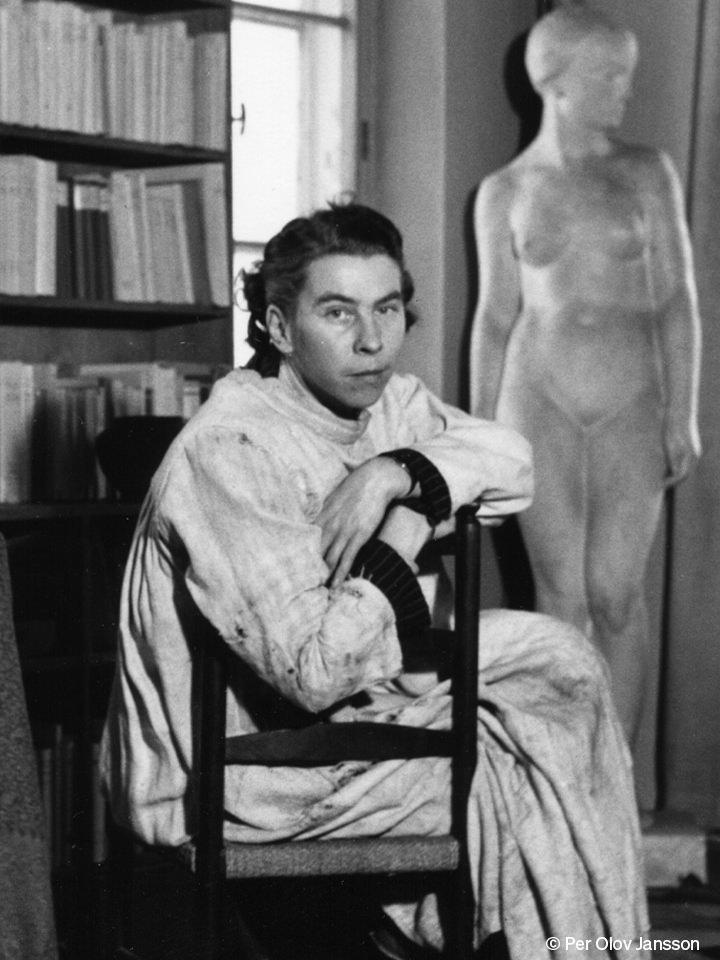

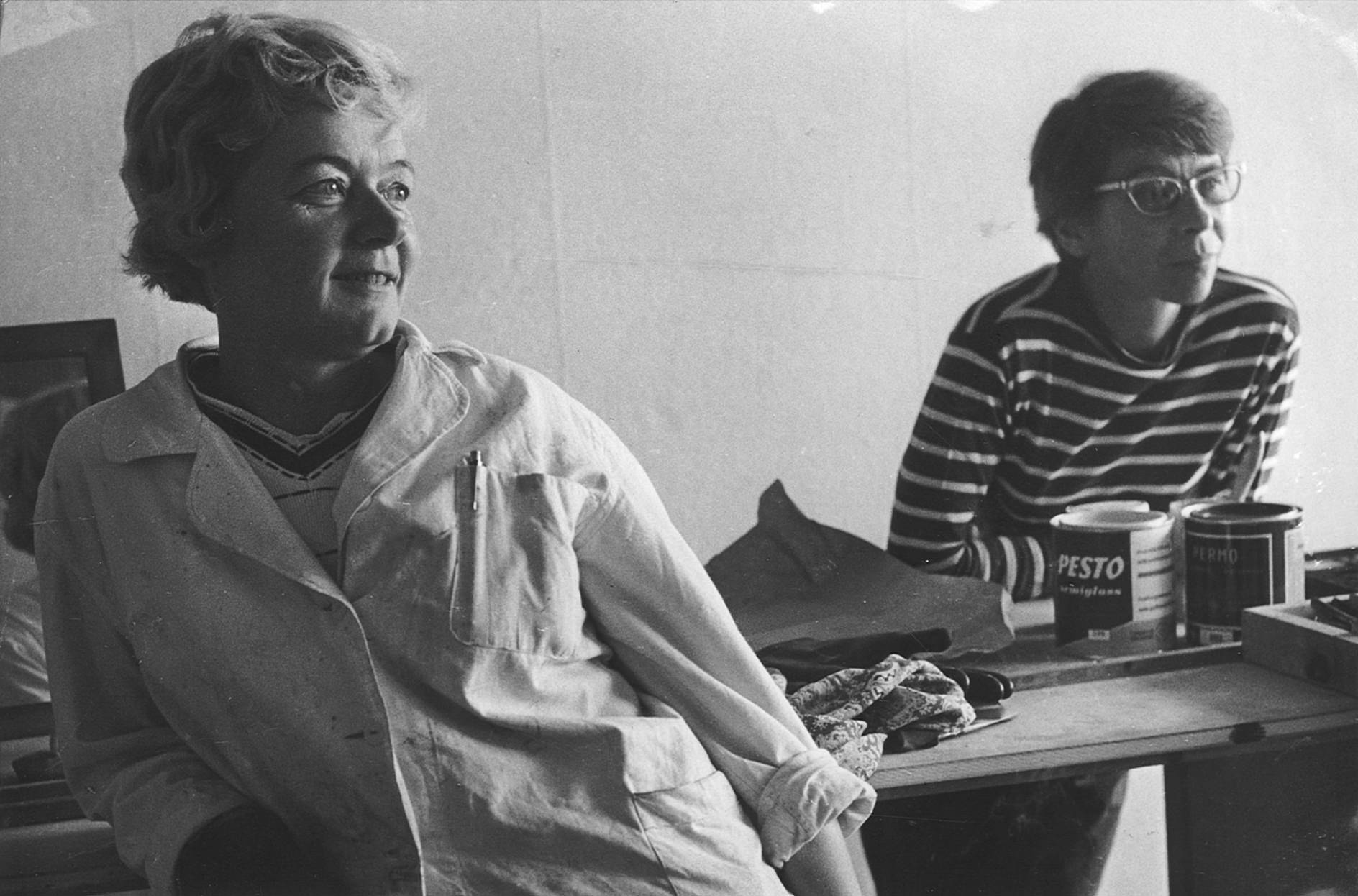

The scene for ‘ghosts’ (slang for lesbian) in the context of artists in Finland, let alone Finland-Swedish artists, is small. In 1952, Tove Jansson, who has felt rootless and been searching for her identity, affirms that she is now sure that she wants to go over to the ghost side, to the rive gauche – in other words, to live as a lesbian – because this is her authentic truth and what will make her happiest. She is living with goldsmith Britt-Sofie Foch at the time and works on portraits and nude studies of her.

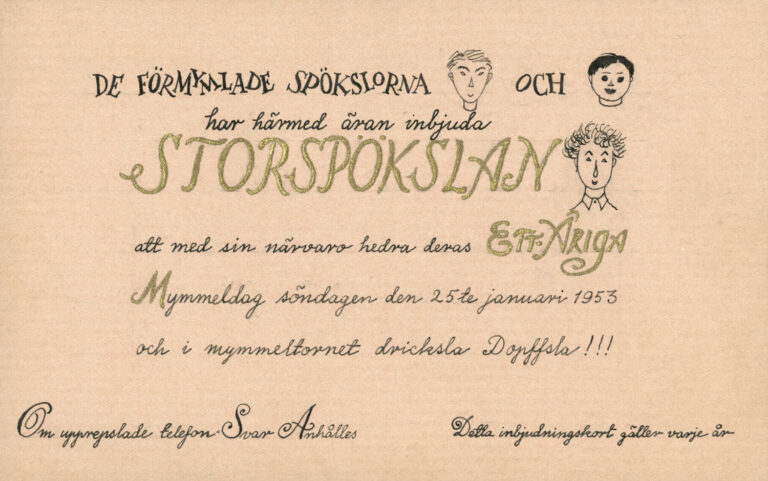

An invitation card from 1953 in which the ghosts Tove Jansson and Britt-Sofie Foch invite the grand ghost Vivica Bandler to grace them with her presence on their first anniversary.

An invitation card from 1953 in which the ghosts Tove Jansson and Britt-Sofie Foch invite the grand ghost Vivica Bandler to grace them with her presence on their first anniversary. When Foch and Bandler meet in Paris, the younger Foch gets advice on everything from clothes to manners and gestures related to being a ghost and how to ‘mymla’. Mymla is a code word for sex and is the origin of Mymlan, Mymble’s name in Swedish. In such small circles, it is easy for relationships to get complicated, and important to be discreet.

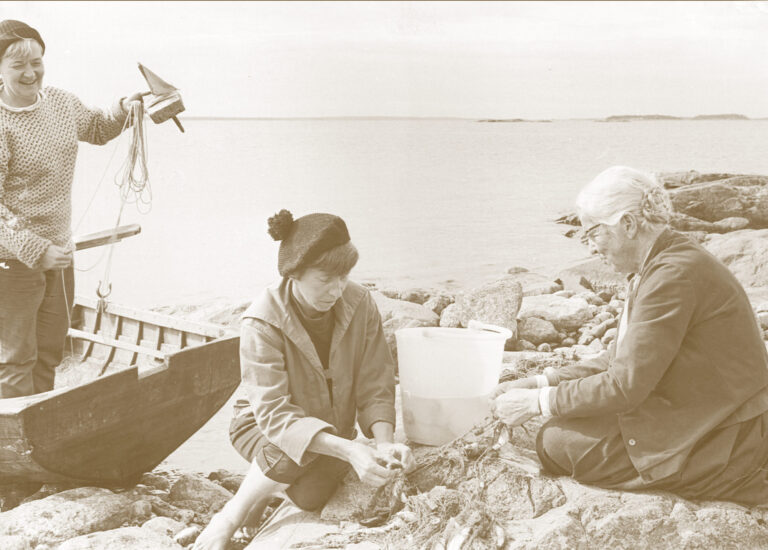

Much is insinuated and read between the lines. Tove Jansson never has a fully open conversation about her feelings with her parents Signe Hammarsten Jansson and Viktor Jansson, which is a reflection of society’s attitude at the time, and the cause of a great sense of isolation. But the various objects of her affection, and their partners, traverse the rocks of Pellinge, and liaisons can be assumed. None of these companions seem to be of a calm demeanour, so their visits no doubt entail great intrigue to weather and emotions to discuss, raucous parties and sunny excursions.

“Vi, I myself am a sun”

Falling in love has changed Tove Jansson. So says her friend Eva Wichman: “You’re different through and through, your manner, your face, the way you move – maybe your thoughts?” (Jansson relates Wichman’s words in a letter to Bandler 29/12/1946). At this point in time, homosexuality is illegal in Finland, and Jansson includes in her letters instructions to burn after reading.

Previously, Tove Jansson has waited for others to approach her and encourage her to bask in the sunshine, whereas with Bandler, she feels already filled with warmth and radiance: “Vi, I myself am a sun.” (Letter to Vivica Bandler) Layers of self-deception and naivety are peeled away to reveal a bold confidence. The communication they share is special, and they fulfil each other’s needs for eroticism, tenderness and understanding.

Alas, Vivica Bandler is soon to depart on a long-planned trip abroad this Christmas. In Tove Jansson’s many love letters to her, she expresses that she is happier than ever. “It is only that happiness is always so serious.” (Letter to Vivica Bandler) Love is not only footloose and fancy-free, but also about loyalty and security. That same evening, she tells Atos Wirtanen, her fiancé at the time, that she no longer loves him.

Al fresco and Songs for my Beloved

Agronomist and director Vivica Bandler is married to Kurt Bandler and has mistresses in Helsinki and Paris. Their whirlwind love affair ends in heartbreak for Tove. To avoid arousing suspicion, several days’ worth of letters are sent in one envelope and the address is written by different people each time, from the local shop or hairdresser. Tove Jansson writes about Thingumy and Bob, who speak a language of their own, in what will become Finn Family Moomintroll, and composes love poems that she wishes she could set to music. She also starts planning two large murals for Helsinki City Hall, commissioned by Vivica Bandler’s father, local politician Erik von Frenckell.

While Jansson is painting her first fresco, Bandler is directing her first film in Paris. Tove Jansson’s friend and mentor Sam Vanni casts doubt on whether she will have time to complete two 2×6 metre large murals in one spring, but she is bold and unfazed. She is keen to prove that she is capable! Johannes Gebhard, teacher of material science at Finnish Art Society’s Drawing School (Ateneum), agrees that it is the opportunity of a lifetime. The task unites her identity and integrity, while also communicating what her beloved means to her. In Party in the City, a very recognisable image of Vivica Bandler dances in the foreground. When Bandler forsakes Tove Jansson for other lovers, her disappointment is great. Their period of happiness is bordered by dark carmine, just as love is edged with darkness.

“Her dress is painted bright and fine

as was our time so glad,

but all around is dark carmine

and the blackest paint I had.”

(“Al Fresco” from Visor till min käresta, translated by Annie Prime)

Visor till min käresta (Songs for my Beloved, later titled Visor till min dam, Songs for my Lady) is an unpublished collection of verses expressing pain, longing, intense joy, admiration and profound melancholy. Tove Jansson sends the text to Vivica Bandler the same summer she gives up on their love. In the poems, the narrator merges into her lover’s wallpaper to hide from all the ‘ifs’, ‘shoulds’ and ‘buts’, but finally sails away in a blue boat when she can no longer stand it.

Contramystical lament

Little by little, Jansson and Bandler’s relationship transforms into a close friendship and mutual support. They are both intense characters, curious about people and united by their creative work. They also share a sense of humour. A year after Tove Jansson sent Songs for my Beloved to Vivica Bandler, she sends her a light-hearted, avant-garde illustrated text entitled Fittornas återtåg (Return of the Cunts).

“Return of the cunts

or

Contramystical lament under extreme circumstances

Psychological sexual tragedy in one act with cockful scenery,

intended for minors of poor disposition at Christmas time,

by Thingumy”

It is a romantic piece mixing Dadaism with the underground, with cut-out images of scantily clad ladies and gentlemen. It’s an example of burlesque humour. The mood is good-natured and light-hearted, and the plot revolves around the Pro Vivica association, headed up by Vivica, busy recruiting new members who must be careful not to fall in love with her.

Friends and Mymbles

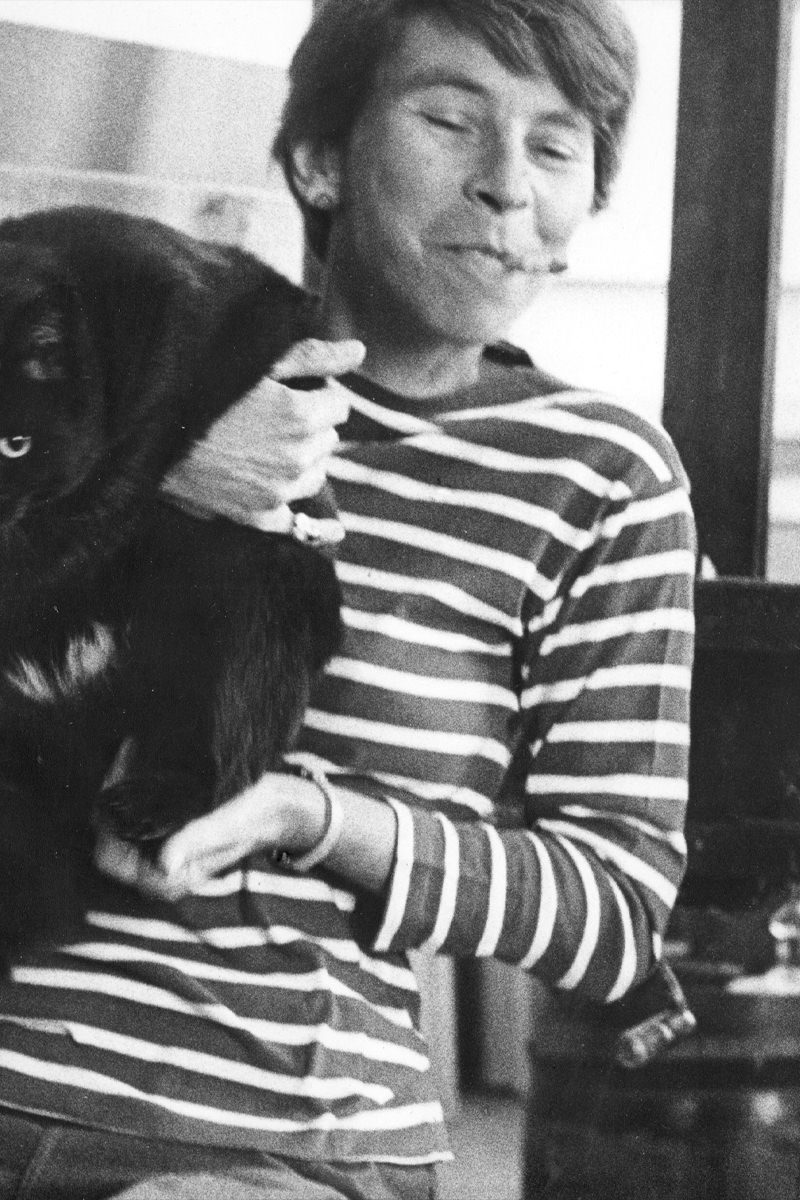

The scene for ‘ghosts’ (slang for lesbian) in the context of artists in Finland, let alone Finland-Swedish artists, is small. In 1952, Tove Jansson, who has felt rootless and been searching for her identity, affirms that she is now sure that she wants to go over to the ghost side, to the rive gauche – in other words, to live as a lesbian – because this is her authentic truth and what will make her happiest. She is living with goldsmith Britt-Sofie Foch at the time and works on portraits and nude studies of her.

When Foch and Bandler meet in Paris, the younger Foch gets advice on everything from clothes to manners and gestures related to being a ghost and how to ‘mymla’. Mymla is a code word for sex and is the origin of Mymlan, Mymble’s name in Swedish. In such small circles, it is easy for relationships to get complicated, and important to be discreet.

Much is insinuated and read between the lines. Tove Jansson never has a fully open conversation about her feelings with her parents Signe Hammarsten Jansson and Viktor Jansson, which is a reflection of society’s attitude at the time, and the cause of a great sense of isolation. But the various objects of her affection, and their partners, traverse the rocks of Pellinge, and liaisons can be assumed. None of these companions seem to be of a calm demeanour, so their visits no doubt entail great intrigue to weather and emotions to discuss, raucous parties and sunny excursions.