FREEDOM AND SHELTER ON KLOVHARUN

Island mentality

In the summer of 1963, Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä spend their first night on Klovharun in a tent. It is a stormy night with crashing waves like cannon blasts. The outer rocks are hit by ominous flashes reminiscent of Bengal lights, far worse than inland, and strong gusts almost destroy their tent. Storms can be a positive force, encouraging people to stretch further and reach beyond their limits. It seems unfeasible to construct a cabin in such an exposed location, but their dream of building a house out here is only growing stronger.

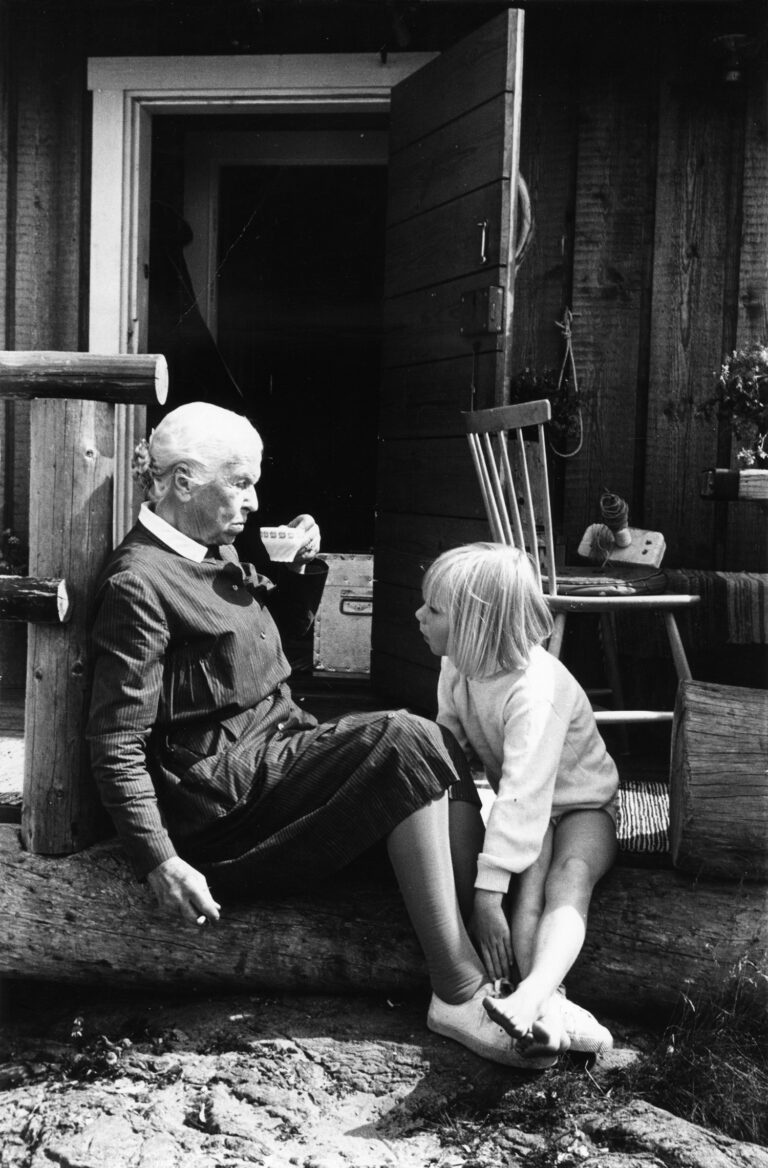

Inland, where they have holidayed the last few summers, Tove Jansson’s mother Signe Hammarsten Jansson, Ham, mourns that things are changing. Tove Jansson is driven to great guilt, which threatens to destroy her and Tooti’s serene solitude on the island. Tove Jansson wants to make sure that everyone is happy, including Ham.

The first island Tove Jansson planned to inhabit was Kummelskär, where she wanted to become a lighthouse keeper, but that dream was dashed. She cannot define why islands have taken on such significance, but she has heard somewhere that ‘ghosts’ (as she calls lesbians) tend to have island mentalities because of an entrenched sense of isolation. The island is remote and bounded, completely private, surrounded by nothing but sea. It is satisfying to limit their environment by walking a complete lap around the island to form a perfect circle.

Tove Jansson's and Tuulikki Pietilä's boat Victoria moored at their island Klovharun.

Tove Jansson's and Tuulikki Pietilä's boat Victoria moored at their island Klovharun. Love for an island

Construction on the island is carried out with the help of local residents Brunström and Sjöblom in 1964-1965, but when the cabin is ready, Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä still continue to sleep in their tent. Indoors, the single room becomes a combined study, living room and guest room. The tent in the yard is yellow and blue and requires regular patching and mending. They go fishing in their strong, beautiful boat Victoria, and catch plenty of cod, which is awkward and gets tangled in the net. When it is too foggy to fish, they set up cat nets close to land.

Seagulls and terns squawk. Harun has always belonged to them really. The smooth underwater stone slabs on the coast are reminiscent of happy childhood summers, and Tove Jansson overturns rocks to uncover the most beautiful stones, careful to return them to their rightful place after winter. Sometimes her relationship with the island is like unrequited love: the island doesn’t necessarily like its inhabitants, or perhaps it pities them. Jansson and Pietilä tidy the islands’ weeds to let stifled flowers bloom. The flowers fill the meadow in a beautiful abundance quite different from the land’s original untouched nature.

Construction work for the cottage at Tove Jansson's and Tuulikki Pietilä's island Klovharun started in 1964.

Construction work for the cottage at Tove Jansson's and Tuulikki Pietilä's island Klovharun started in 1964. The significance of freedom

Why such an intense need for freedom? In 1972, Tove Jansson writes about the importance of freedom for the magazine PHP, and muses on the childlike, irresponsible freedom of Snufkin, which everybody has the capacity for deep down. Over the course of the Moomin stories, Snufkin’s conscience grows, and his state of solitude wanes in appeal. Nothing is immutable – one also needs the freedom to make mistakes, start again and try something new.

The idea of freedom also relates to creative work and the people one shares one’s life with. The greatest challenge is to maintain solitude and integrity when surrounded by other people. The Moomin family represents a sort of utopia in which everyone allows each other total freedom – freedom to be alone, to form their own opinions, and to keep secrets until those secrets are ready to be revealed. The Moomins don’t make each other feel bad.

Everyday life on the island continues gently and with enough quiet to occasionally verge on being boring. Then nieces come to visit, running around blowing soap bubbles and livening things up. All sorts of guests come to stay, both expected and unexpected: Moomin fans, researchers, interviewers, friends and family. A moonshadow can change everything in a heartbeat, and one memorable night a powerful tornado passes through, powerful enough to sweep the island’s buildings away entirely.

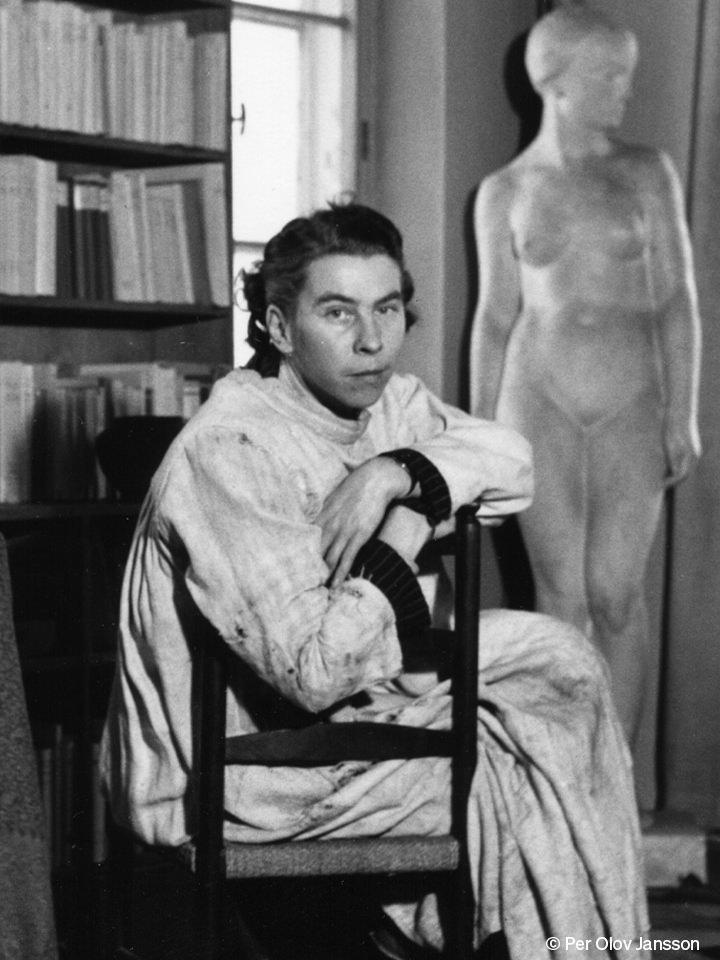

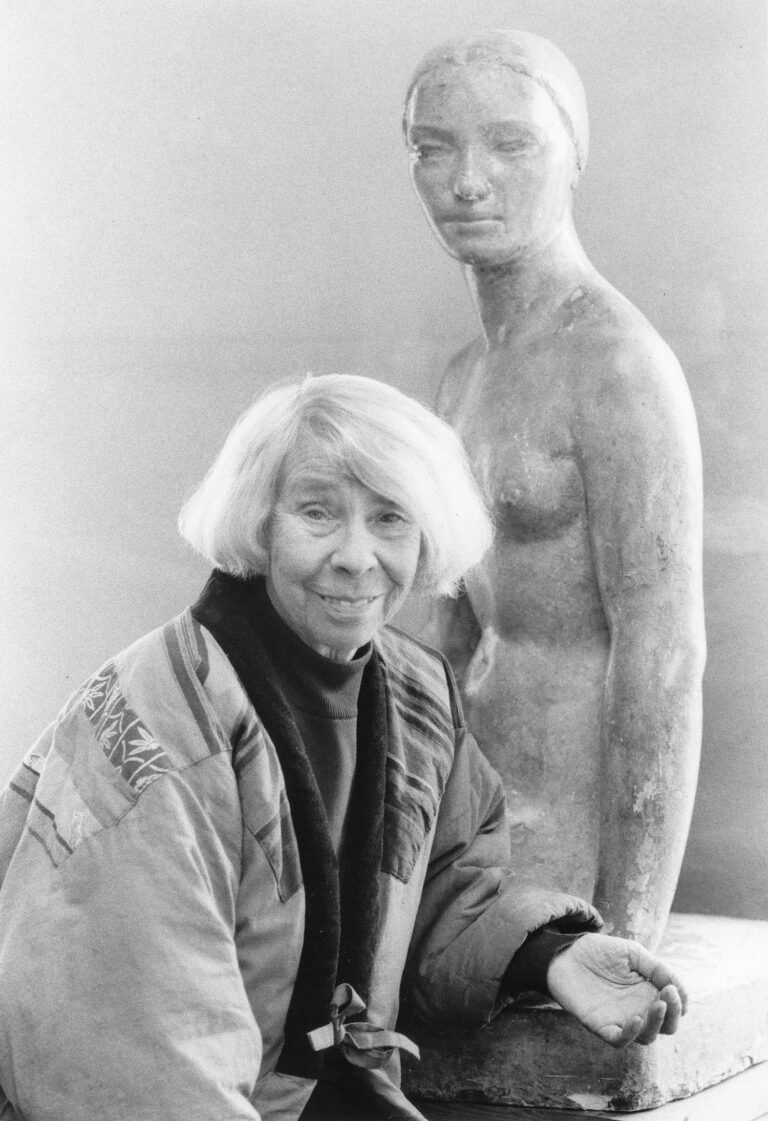

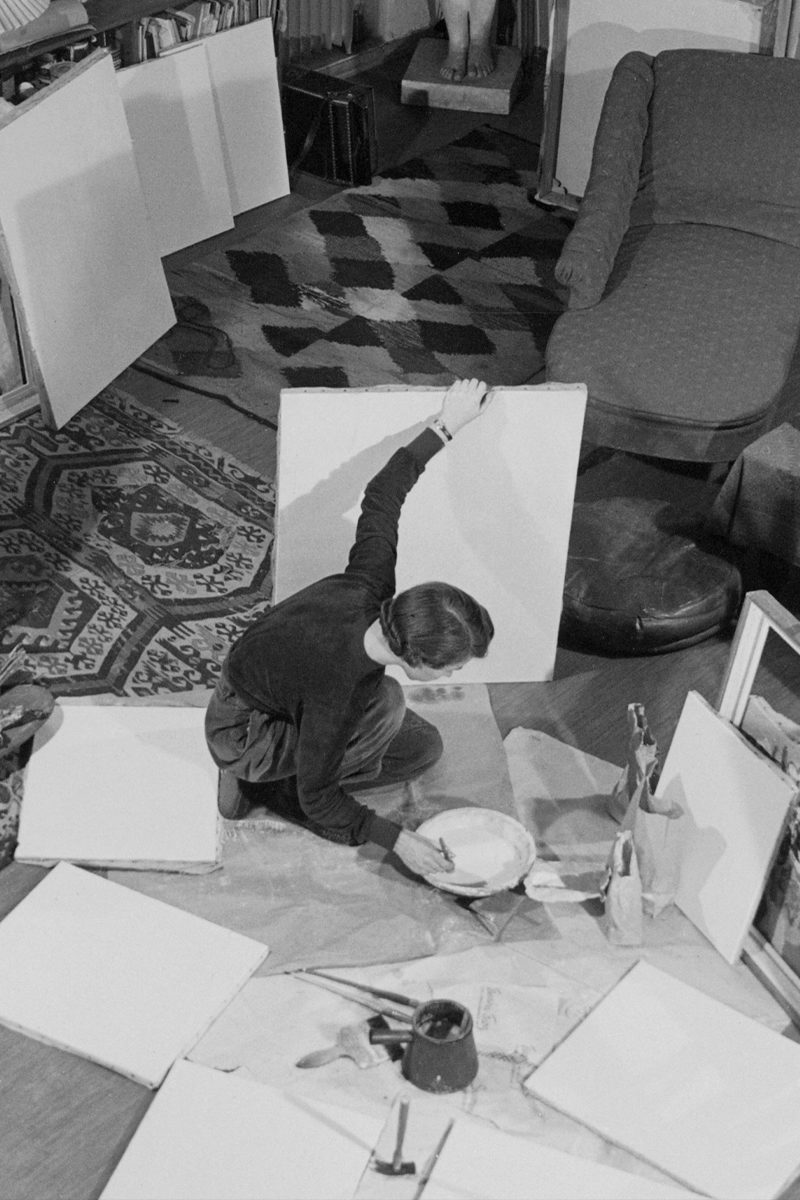

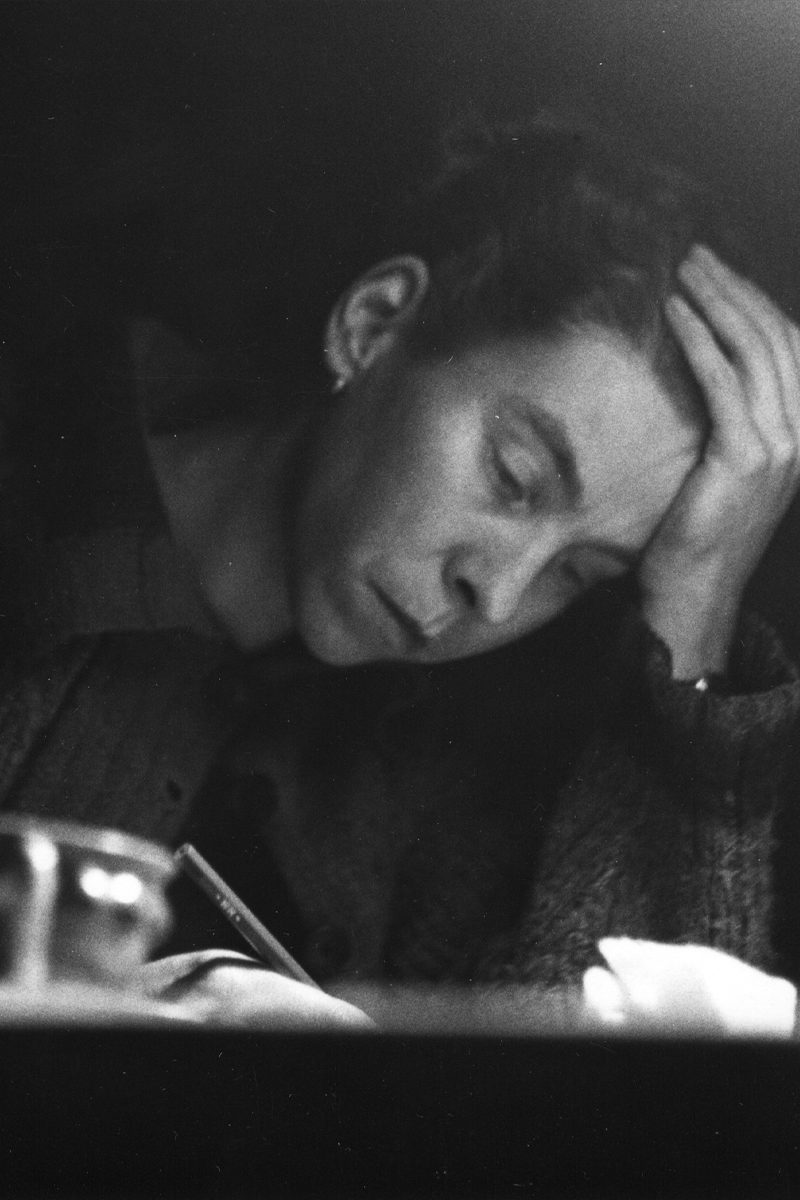

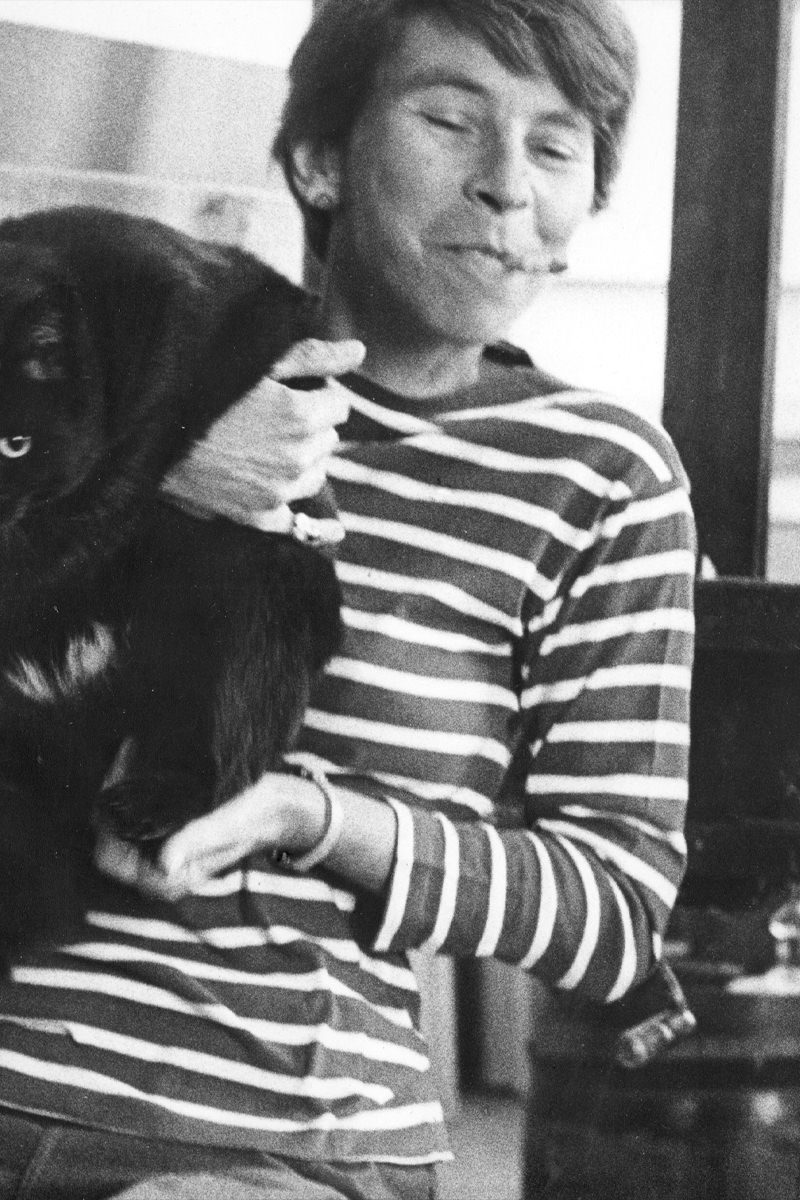

Tove Jansson in her summer paradise, the Klovharun island in 1966.

Tove Jansson in her summer paradise, the Klovharun island in 1966. Everyday security

“When you’ve been alone for a very long time, you begin to listen differently, to feel the organic and the unexpected in your surroundings, and to see the incomprehensible beauty of the material world in everything.

Old entrenched thoughts leap out in new directions, or they shrink and die. Dreams grow simpler, and you wake up smiling.

It is a fragile structure. You pay for it with fear of the dark and sudden panic—a rustling in the darkness, a boat on the horizon.

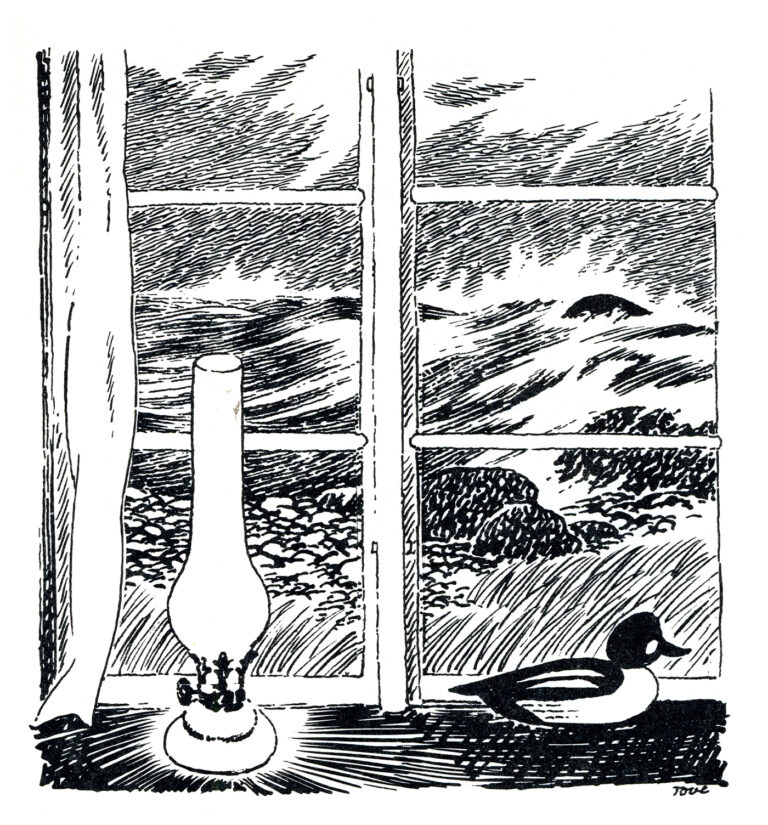

But at the same time, your calmly repeated, purposeful, everyday acts build a protective wall that grows higher and more stable. Pulling up your boat before a storm, lighting your lamp for the night, collecting and chopping wood. ” (From the essay “The Island”)

The scurvy grass first blooms in spring and often causes problems when the wind blows from the south-west. The island has its own routines and cycles. Even the regular rise and fall of the water is significant and satisfying. Tove Jansson’s island poetry speaks of life and creation.

Island mentality

In the summer of 1963, Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä spend their first night on Klovharun in a tent. It is a stormy night with crashing waves like cannon blasts. The outer rocks are hit by ominous flashes reminiscent of Bengal lights, far worse than inland, and strong gusts almost destroy their tent. Storms can be a positive force, encouraging people to stretch further and reach beyond their limits. It seems unfeasible to construct a cabin in such an exposed location, but their dream of building a house out here is only growing stronger.

Inland, where they have holidayed the last few summers, Tove Jansson’s mother Signe Hammarsten Jansson, Ham, mourns that things are changing. Tove Jansson is driven to great guilt, which threatens to destroy her and Tooti’s serene solitude on the island. Tove Jansson wants to make sure that everyone is happy, including Ham.

The first island Tove Jansson planned to inhabit was Kummelskär, where she wanted to become a lighthouse keeper, but that dream was dashed. She cannot define why islands have taken on such significance, but she has heard somewhere that ‘ghosts’ (as she calls lesbians) tend to have island mentalities because of an entrenched sense of isolation. The island is remote and bounded, completely private, surrounded by nothing but sea. It is satisfying to limit their environment by walking a complete lap around the island to form a perfect circle.

Love for an island

Construction on the island is carried out with the help of local residents Brunström and Sjöblom in 1964-1965, but when the cabin is ready, Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä still continue to sleep in their tent. Indoors, the single room becomes a combined study, living room and guest room. The tent in the yard is yellow and blue and requires regular patching and mending. They go fishing in their strong, beautiful boat Victoria, and catch plenty of cod, which is awkward and gets tangled in the net. When it is too foggy to fish, they set up cat nets close to land.

Seagulls and terns squawk. Harun has always belonged to them really. The smooth underwater stone slabs on the coast are reminiscent of happy childhood summers, and Tove Jansson overturns rocks to uncover the most beautiful stones, careful to return them to their rightful place after winter. Sometimes her relationship with the island is like unrequited love: the island doesn’t necessarily like its inhabitants, or perhaps it pities them. Jansson and Pietilä tidy the islands’ weeds to let stifled flowers bloom. The flowers fill the meadow in a beautiful abundance quite different from the land’s original untouched nature.

The significance of freedom

Why such an intense need for freedom? In 1972, Tove Jansson writes about the importance of freedom for the magazine PHP, and muses on the childlike, irresponsible freedom of Snufkin, which everybody has the capacity for deep down. Over the course of the Moomin stories, Snufkin’s conscience grows, and his state of solitude wanes in appeal. Nothing is immutable – one also needs the freedom to make mistakes, start again and try something new.

The idea of freedom also relates to creative work and the people one shares one’s life with. The greatest challenge is to maintain solitude and integrity when surrounded by other people. The Moomin family represents a sort of utopia in which everyone allows each other total freedom – freedom to be alone, to form their own opinions, and to keep secrets until those secrets are ready to be revealed. The Moomins don’t make each other feel bad.

Everyday life on the island continues gently and with enough quiet to occasionally verge on being boring. Then nieces come to visit, running around blowing soap bubbles and livening things up. All sorts of guests come to stay, both expected and unexpected: Moomin fans, researchers, interviewers, friends and family. A moonshadow can change everything in a heartbeat, and one memorable night a powerful tornado passes through, powerful enough to sweep the island’s buildings away entirely.

Everyday security

“When you’ve been alone for a very long time, you begin to listen differently, to feel the organic and the unexpected in your surroundings, and to see the incomprehensible beauty of the material world in everything.

Old entrenched thoughts leap out in new directions, or they shrink and die. Dreams grow simpler, and you wake up smiling.

It is a fragile structure. You pay for it with fear of the dark and sudden panic—a rustling in the darkness, a boat on the horizon.

But at the same time, your calmly repeated, purposeful, everyday acts build a protective wall that grows higher and more stable. Pulling up your boat before a storm, lighting your lamp for the night, collecting and chopping wood. ” (From the essay “The Island”)

The scurvy grass first blooms in spring and often causes problems when the wind blows from the south-west. The island has its own routines and cycles. Even the regular rise and fall of the water is significant and satisfying. Tove Jansson’s island poetry speaks of life and creation.