The basic philosophy of Moominvalley

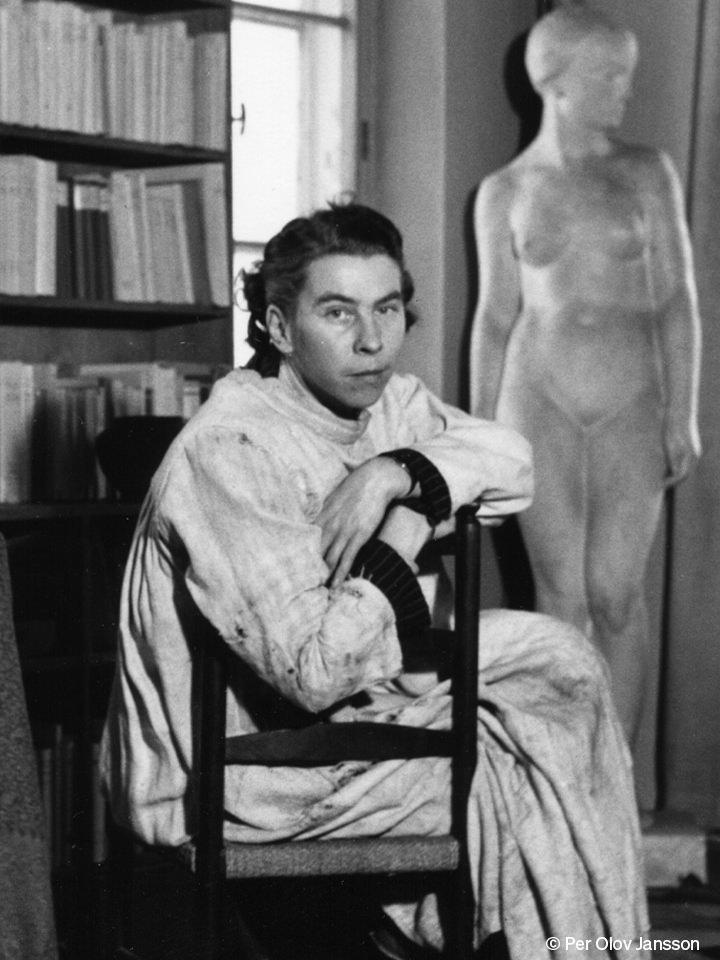

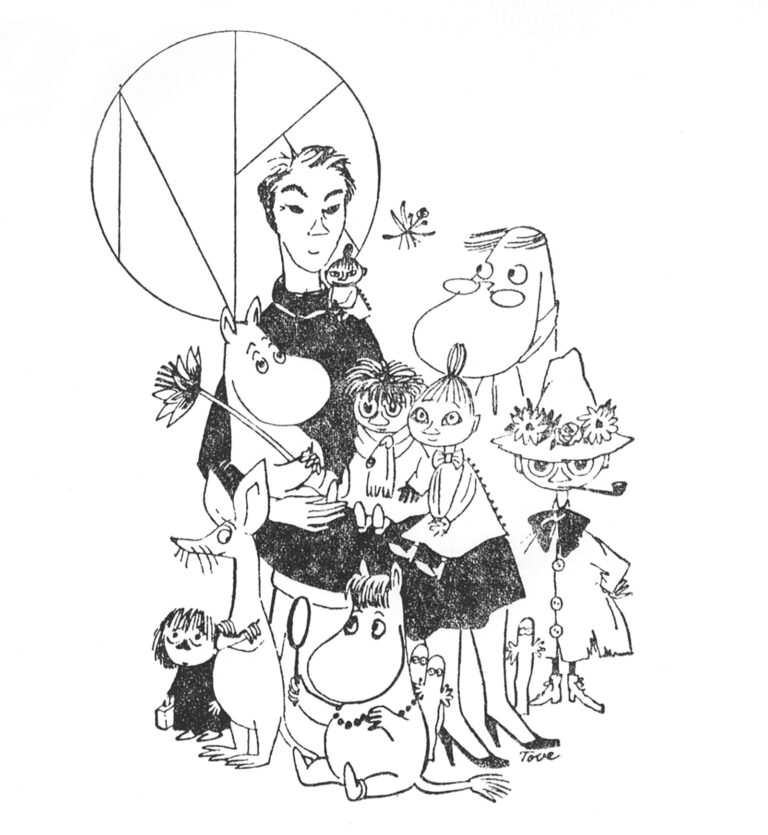

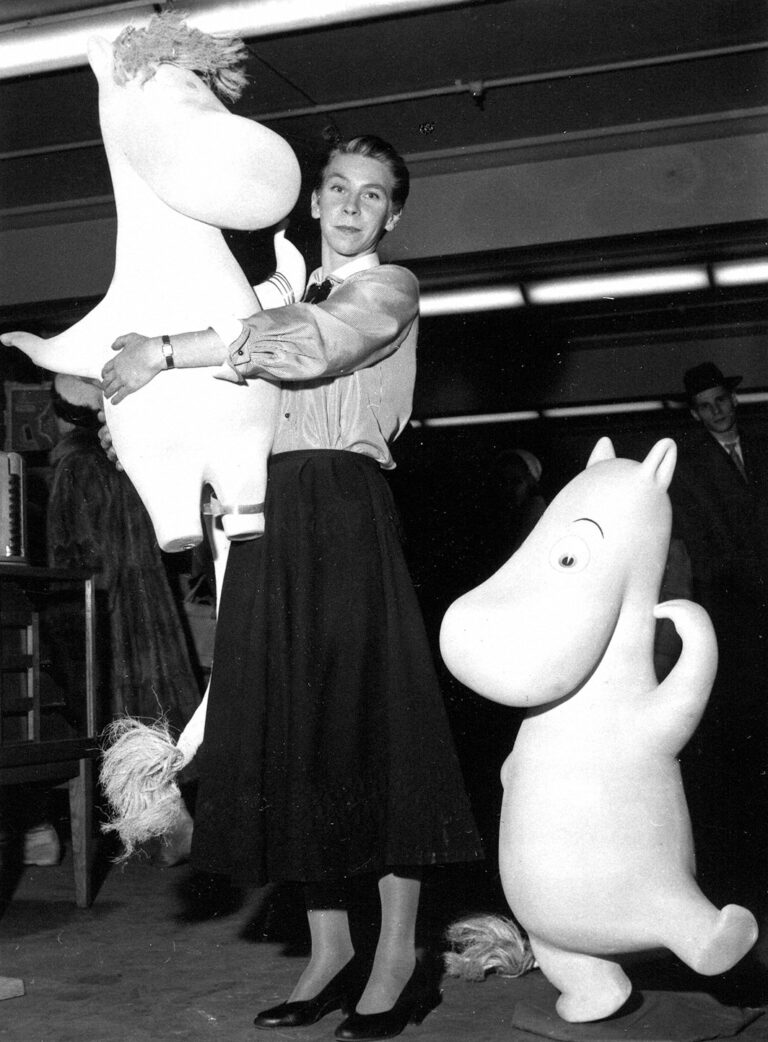

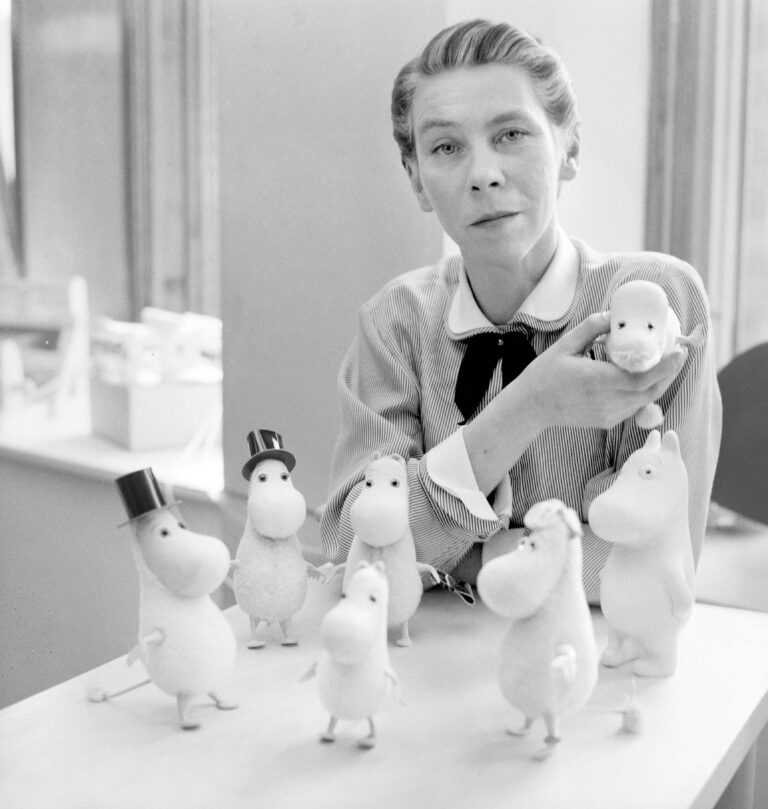

In the beginning, Moomintroll has a longer, sharper nose and is called ‘snork’. The character appears as a dark, shadowy figure in Tove Jansson’s pictures and becomes her trademark in the satirical magazine Garm. The figure can also be found even earlier, graffitied on an outhouse wall in response to a philosophical debate.

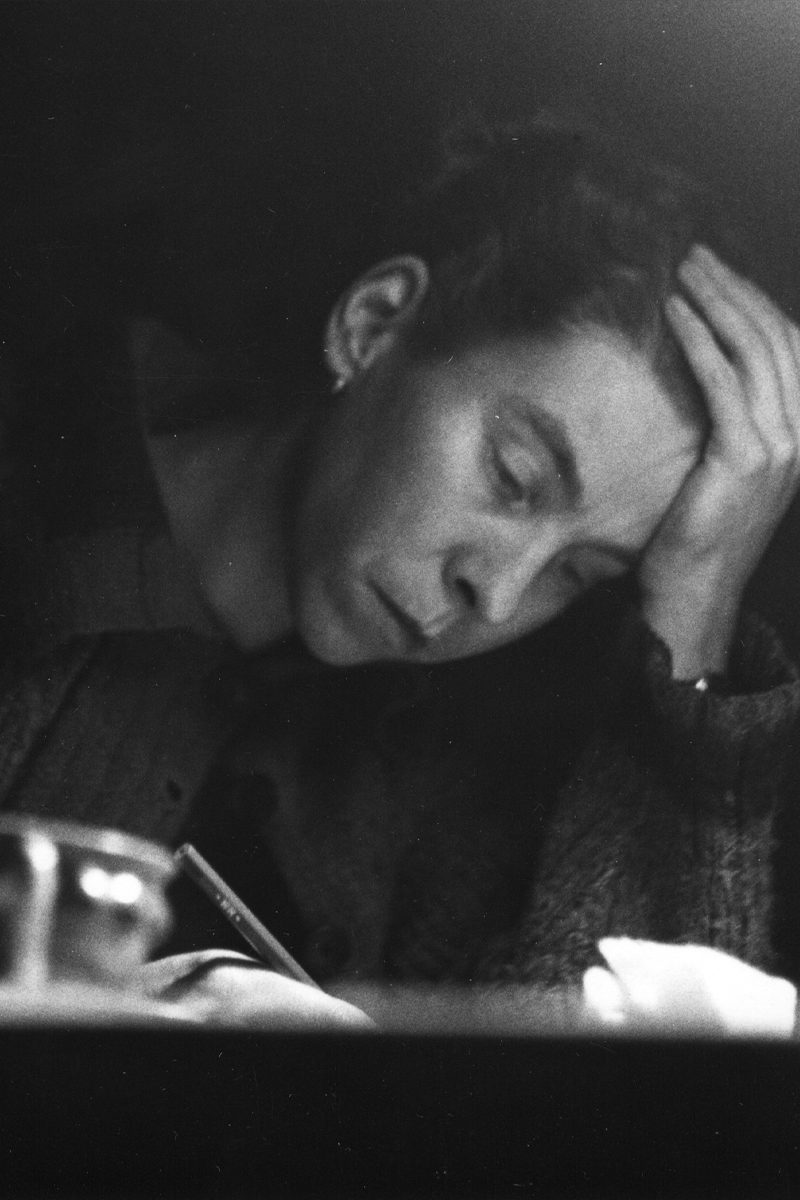

Tove Jansson writes the first Moomin story The Moomins and the Great Flood in the 1940s, a time of war and poverty, when children’s stories are rare. Even before its publication, she starts sketching her next book, while staying in Atos Wirtanen’s villa in Kauniainen. Perhaps she finds her inspiration there in the promise of a happier time.

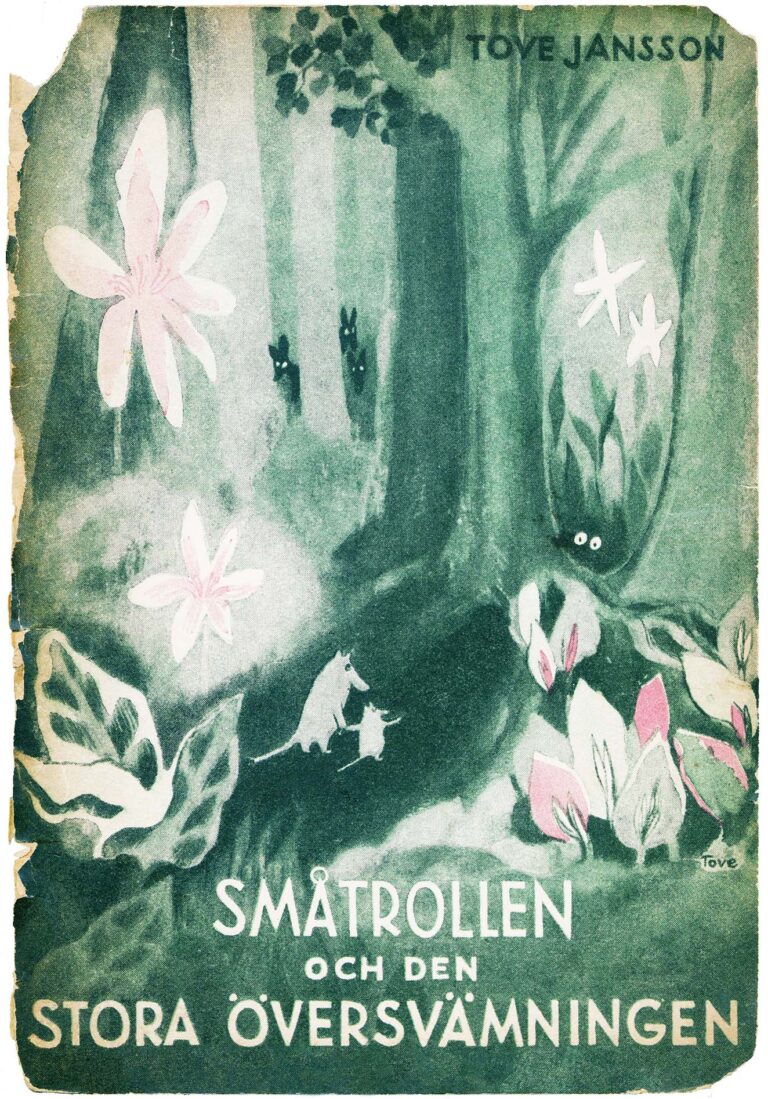

Tove Jansson’s book cover for the original Swedish version of the first Moomin story The Moomins and the Great Flood, 1945.

Comet in Moominland

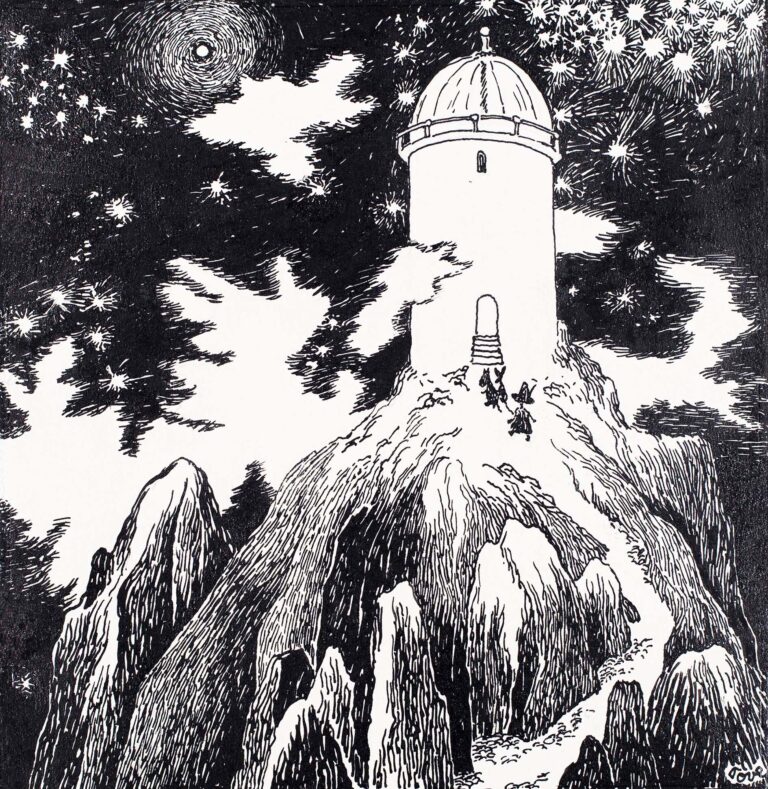

Tove Jansson sketches rocky mountains, starry skies, comets and an observatory similar to the one she knows from Kaivopuisto in Helsinki. The shape of Moomin becomes rounder, softer. Her work culminates in the chapter book Comet in Moominland, about a comet that has veered off course and is heading straight for Moominvalley. Moomintroll and Sniff head to the observatory to find out more. On their way, they meet Snufkin, who becomes Moomin’s best friend, and then Snorkmaiden, who becomes his love interest. Snork and Hemulen also join the gang, giving Moomin a fulsome community.

Faced with a row of disasters, big and small, the friends rescue each other from falling into a pit in the Lonely Mountains, from the terrible Angostura and a giant octopus. The friends survive by helping each other. Snufkin helps to remind Moomin of the things that really matter, namely art and the beauty of nature. He also convinces Moomintroll and Sniff to free themselves from their awkward, materialistic luggage.

The observatory in Tove Jansson’s book Comet in Moominland, 1946.

The Muskrat philosopher

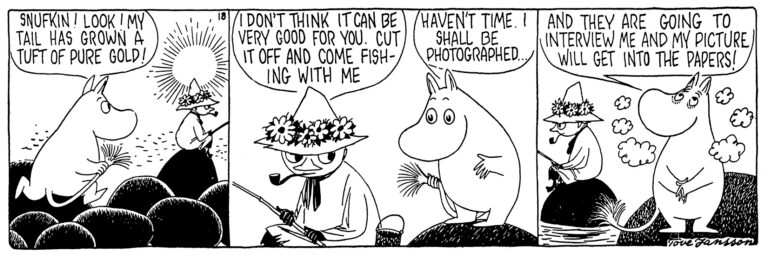

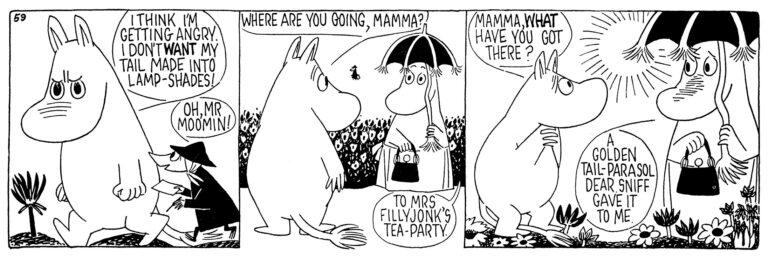

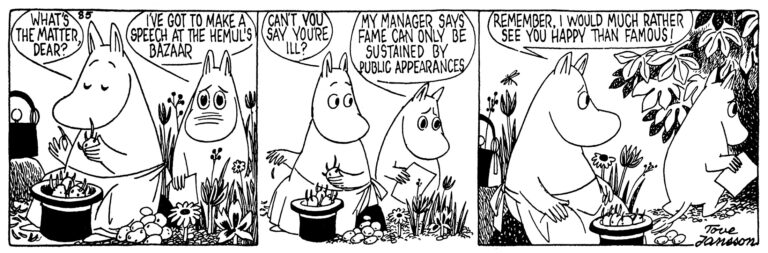

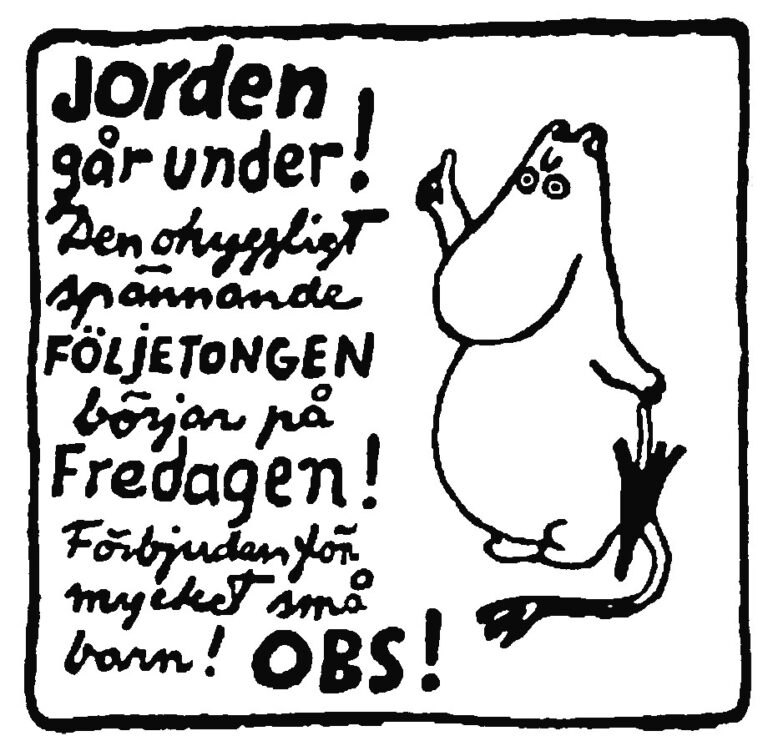

Atos Wirtanen, editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper Ny Tid, and Tove Jansson’s boyfriend at the time, decides that his paper needs a comic strip, as has become common in American papers. No sooner said than done, Tove gets to work writing and drawing, and the first series Moomintroll and the End of the World appears on the children’s pages.

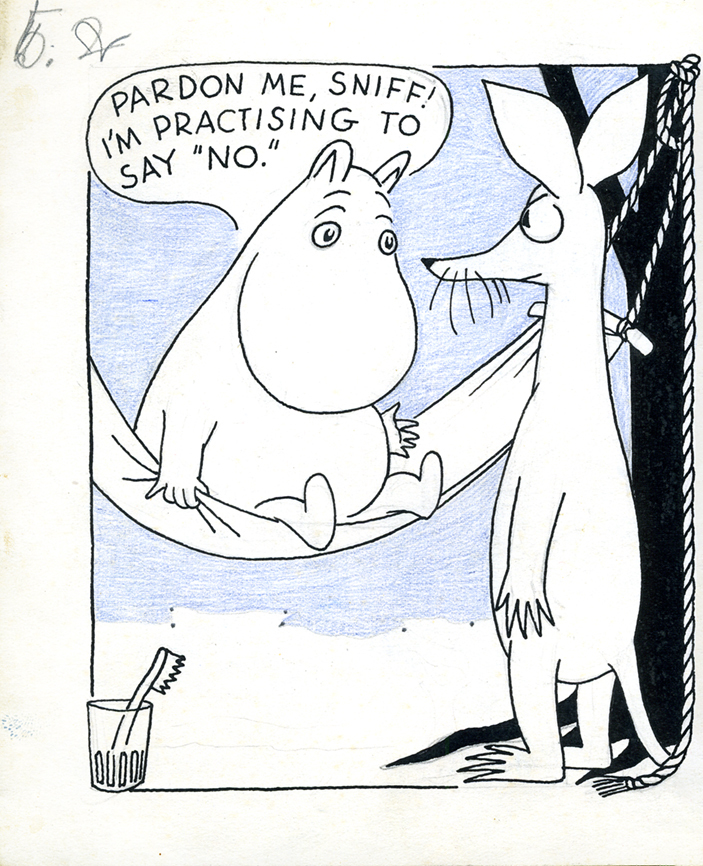

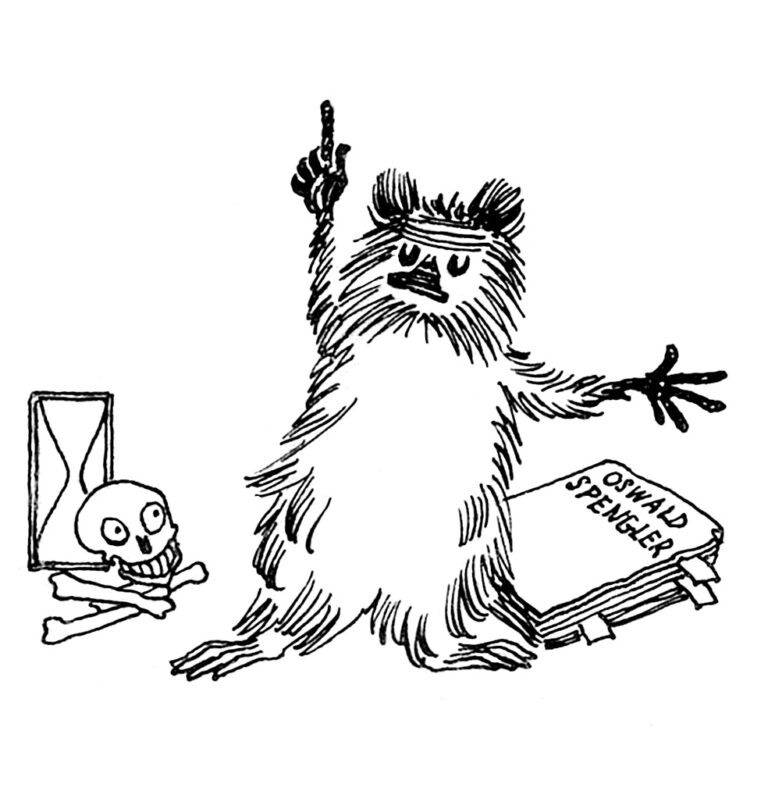

It begins much like Comet in Moominland, with a great storm and the grumpy, boozing Muskrat telling the Moomin family about the impending comet. As the family goes out of their minds with worry, the Muskrat lies down in a hammock to read a book by Oswald Spengler about the decline of the West.

Tove Jansson’s Muskrat illustration, 1947-48.

Tove Jansson’s first Moomin comic strip in the daily newspaper Ny Tid, 1947.

The Muskrat is a concrete reminder of the omnipresent philosophy and existentialism in Moominvalley. In the marshland near Wirtanen’s villa there is a place they call the “muskrat swamp”, where Wirtanen often goes to ponder philosophical questions. In her letters, Tove Jansson calls Wirtanen alternately “dearest”, “solofif” (a play on the Swedish word for philosopher – filosof) and “mi caro sofo”, and the thoughts of this real-life philosopher are deeply embedded in Moominvalley.

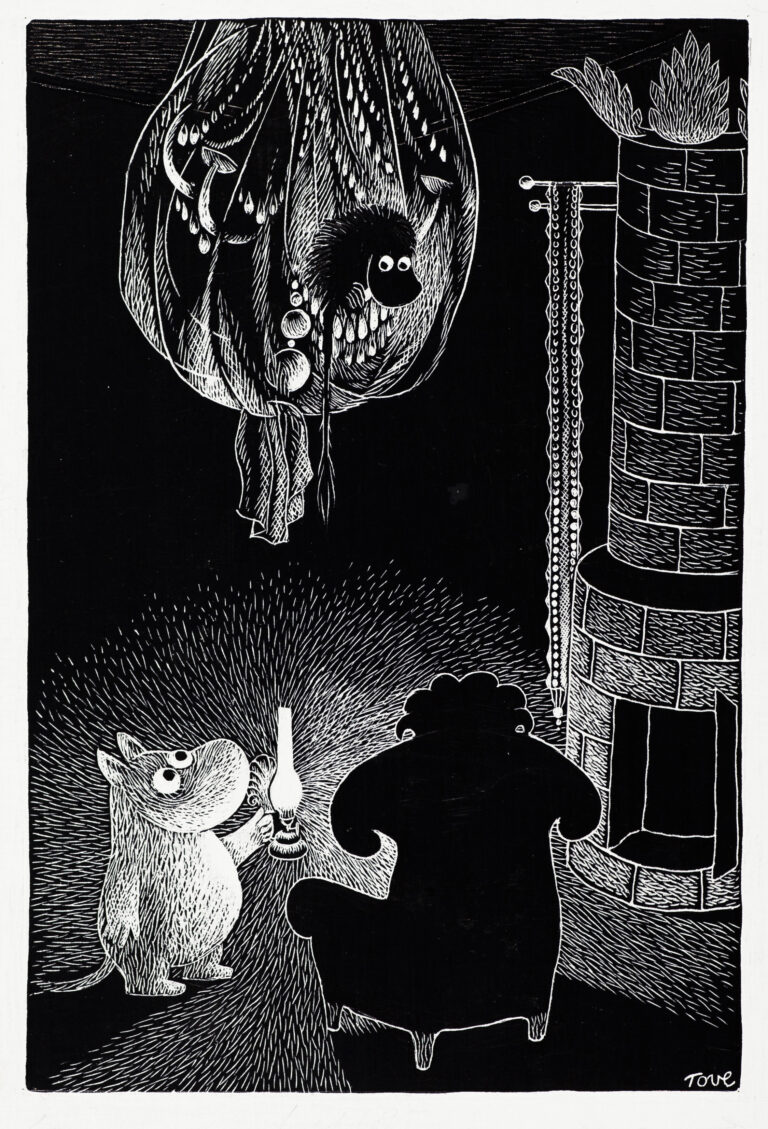

As the comet casts its shadow over Moominvalley, Tove Jansson tells a story about the importance of friendship, art, beauty and community. When the comet finally arrives in Comet in Moominland, Moomin, his family and friends sit in a cave and hold each other close – reminiscent of a bomb shelter during a wartime air raid. Afterwards, it is eerily silent. There, at the intersection of the warmth of a close-knit community and the cruelty of a great comet, lies the basic philosophy of Moominvalley.

Cave illustration in Tove Jansson’s book “Comet in Moominland”, 1946.

In the beginning, Moomintroll has a longer, sharper nose and is called ‘snork’. The character appears as a dark, shadowy figure in Tove Jansson’s pictures and becomes her trademark in the satirical magazine Garm. The figure can also be found even earlier, graffitied on an outhouse wall in response to a philosophical debate.

Tove Jansson writes the first Moomin story The Moomins and the Great Flood in the 1940s, a time of war and poverty, when children’s stories are rare. Even before its publication, she starts sketching her next book, while staying in Atos Wirtanen’s villa in Kauniainen. Perhaps she finds her inspiration there in the promise of a happier time.

Comet in Moominland

Tove Jansson sketches rocky mountains, starry skies, comets and an observatory similar to the one she knows from Kaivopuisto in Helsinki. The shape of Moomin becomes rounder, softer. Her work culminates in the chapter book Comet in Moominland, about a comet that has veered off course and is heading straight for Moominvalley. Moomintroll and Sniff head to the observatory to find out more. On their way, they meet Snufkin, who becomes Moomin’s best friend, and then Snorkmaiden, who becomes his love interest. Snork and Hemulen also join the gang, giving Moomin a fulsome community.

Faced with a row of disasters, big and small, the friends rescue each other from falling into a pit in the Lonely Mountains, from the terrible Angostura and a giant octopus. The friends survive by helping each other. Snufkin helps to remind Moomin of the things that really matter, namely art and the beauty of nature. He also convinces Moomintroll and Sniff to free themselves from their awkward, materialistic luggage.

The Muskrat philosopher

Atos Wirtanen, editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper Ny Tid, and Tove Jansson’s boyfriend at the time, decides that his paper needs a comic strip, as has become common in American papers. No sooner said than done, Tove gets to work writing and drawing, and the first series Moomintroll and the End of the World appears on the children’s pages.

It begins much like Comet in Moominland, with a great storm and the grumpy, boozing Muskrat telling the Moomin family about the impending comet. As the family goes out of their minds with worry, the Muskrat lies down in a hammock to read a book by Oswald Spengler about the decline of the West.

The Muskrat is a concrete reminder of the omnipresent philosophy and existentialism in Moominvalley. In the marshland near Wirtanen’s villa there is a place they call the “muskrat swamp”, where Wirtanen often goes to ponder philosophical questions. In her letters, Tove Jansson calls Wirtanen alternately “dearest”, “solofif” (a play on the Swedish word for philosopher – filosof) and “mi caro sofo”, and the thoughts of this real-life philosopher are deeply embedded in Moominvalley.

As the comet casts its shadow over Moominvalley, Tove Jansson tells a story about the importance of friendship, art, beauty and community. When the comet finally arrives in Comet in Moominland, Moomin, his family and friends sit in a cave and hold each other close – reminiscent of a bomb shelter during a wartime air raid. Afterwards, it is eerily silent. There, at the intersection of the warmth of a close-knit community and the cruelty of a great comet, lies the basic philosophy of Moominvalley.